First of all, we don’t want any fans of the Gallery to panic – much of the look and feel will remain in the new Natural History Gallery, and the Gallery will retain its historical infrastructure and atmosphere. The rest of the Museum will remain open, so still plenty to see!

One large reason that the Natural History Gallery is being updated is that lots of the interpretation and information surrounding the cases has been untouched for many years and is now very out of date. As new information has come to light in the years since the gallery first opened, the written information within the Gallery has become more and more outdated. Many species names have now changed, for example, since the original interpretation was written.

We also want to make the gallery more accessible, more relevant and to reference the human impact on our planet.

History of taxidermy

Taxidermy is the process of preserving an animal’s skin, fur, feathers, or scales after they have died. In ancient times it was purely a form of preservation, whereas more modern taxidermy is closer to sculpture or art. Modern taxidermy aims to replicate, in model form, the animal when it was alive.

Taxidermy has been around for thousands of years, with examples seen in Ancient Egypt. The Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution in the 16th and 17th centuries saw an increased interest in understanding the science of the natural world. Alongside this, there was a trend in taxidermy and natural history exhibits being displayed naturally – with the animals in their natural habitat.

History of taxidermy in natural history galleries

Taxidermy was particularly popular with the Victorians, who were fascinated with the idea of having a wild animal in their homes.

One of the biggest events to spur on taxidermy in Britain was The Great Exhibition in 1851. This display of exhibits in Hyde Park saw taxidermists from across the world come together for the first time in history. The Great Exhibition was visited by more than a third of the British public.

From the archives

Much of Frederick Horniman’s collections had been on display in the family home, until his wife is said to have declared ‘either the collection goes… or we do’. And so, a purpose-built museum was created, first known as Surrey House Museum and then as the Horniman Museum.

It was founded with the aims of ‘recreation, instruction and enjoyment’.

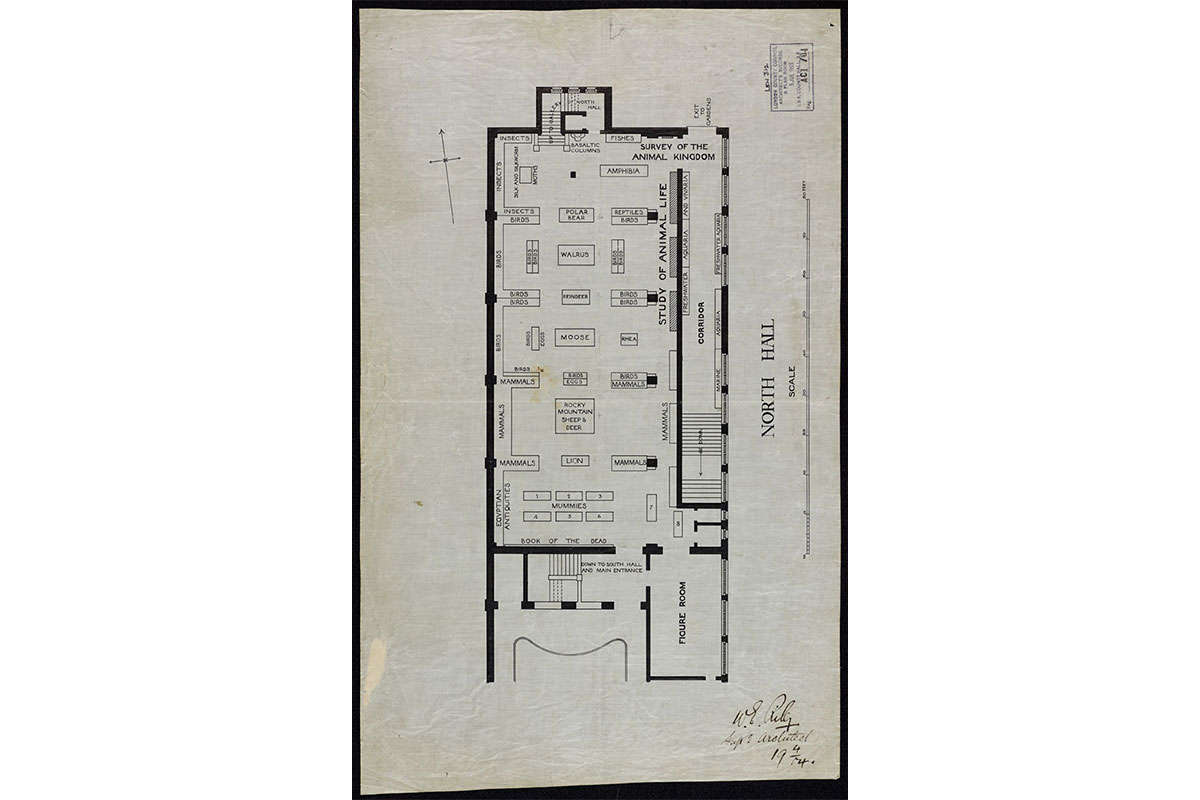

In this floor plan from around 1904 you can see how the cases were labelled and how more specimens were in large cases through the centre of the gallery than there are today. The Walrus, however, still took pride of place.

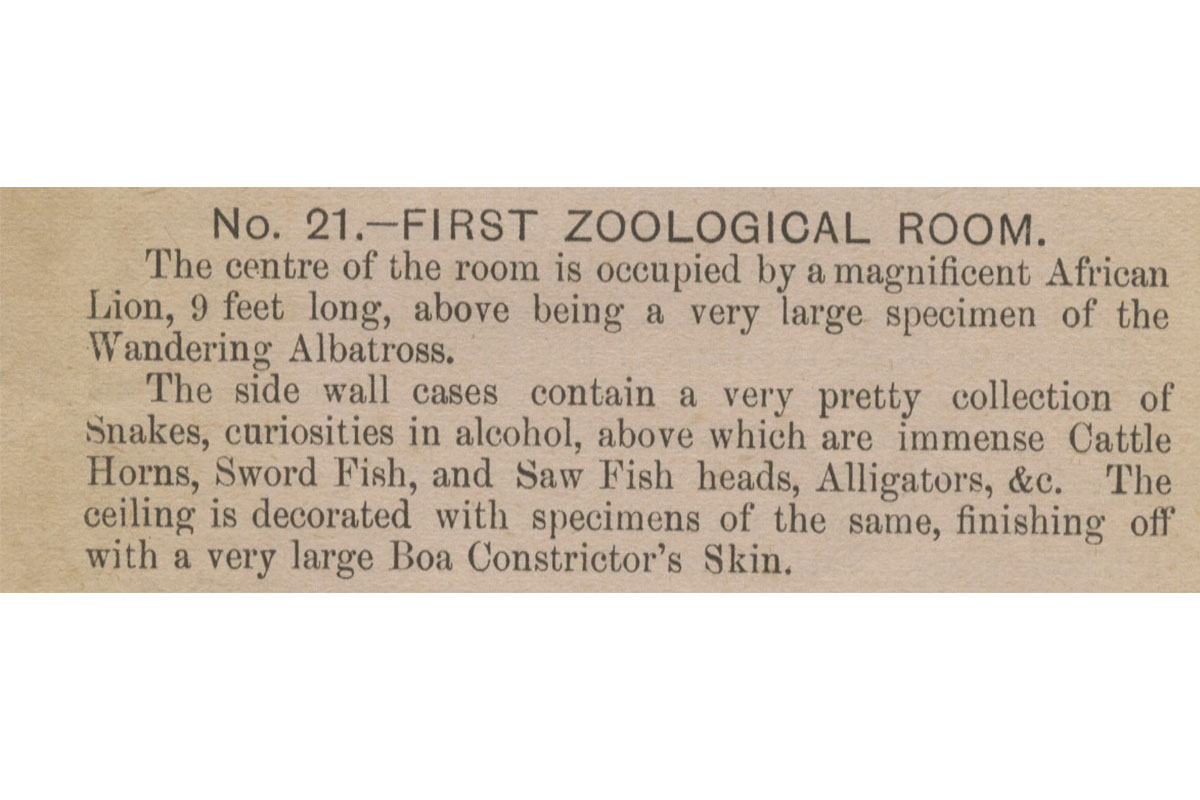

In this page from a Museum guide from before 1897, Frederick Horniman describes to visitors what they can see in the cases in the ‘first zoological room’. These descriptions simply state what is in the Gallery, without offering any extra information or analysis, like you might see in a gallery today.

Windows and cases

The barrel-vaulted ceiling would have housed skylight windows, to allow natural light onto the objects so they could be seen.

This method of lighting the Gallery however meant that many of the objects would have suffered from sun damage. In modern times gallery lighting is carefully monitored to ensure it has the smallest amount of impact on the objects possible. We can see the windows were covered at some point after 1982, as the ceiling windows are visible in this photo in the London Metropolitan Archives.

The cases on the ground floor would also have had glass tops, so that visitors on the balcony could look down into them. You can still see some cases with glass tops today.

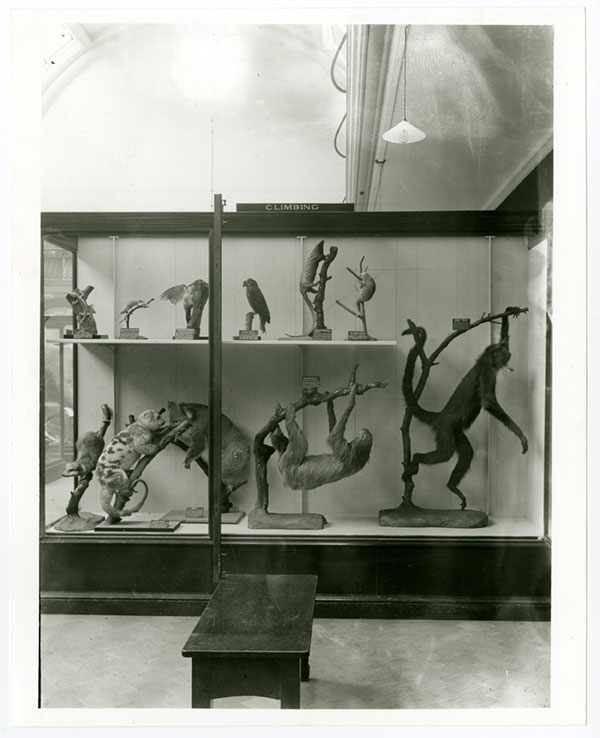

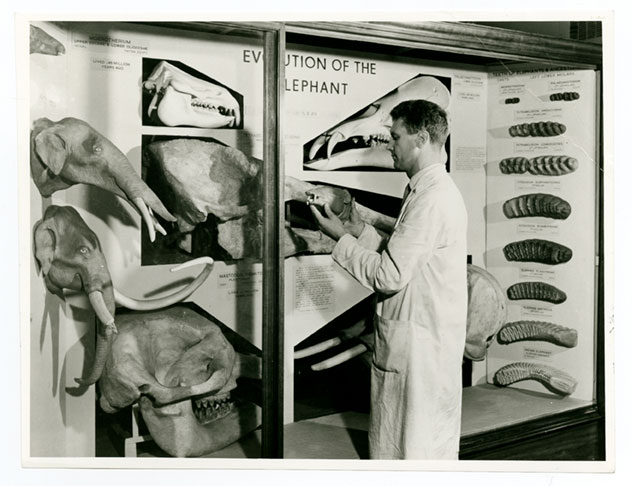

In the second half of the twentieth century curator Frank Winshall modernised many of the cases. The displays today have gone largely unchanged since. His work saw the introduction of bespoke graphics, and a focus on design for educational purposes.

The visitors

Arguably the biggest shift in the Gallery, is how we hope our visitors will interact with it. You can see a perfect of example of this in the extract from the 1905 Annual Report below.

A falling off in number of visitor[s]… at the beginning of April to improve the behaviour of a certain section of them… since a considerable number of irresponsible and frivolous visitors have been discouraged from using the Museum as a promenade, especially on Sunday evenings, the decrease represents an improvement rather than a reverse.

The building itself

Charles Harrison Townsend designed the original buildings, but many of the early plan layouts of the North Hall contain William Edward Riley’s signature. Riley was Chief Architect to London County Council from 1899. He was responsible for the direction of buildings including Central School of Arts and Crafts, many schools across the capital and Sessions House on Newington Causeway.

Live animals

Whilst the Natural History Gallery has long been home to taxidermy specimens, the Horniman also long had a tradition of live animals on display. Alongside what is now the World Gallery and Natural History Gallery runs a corridor, behind the scenes. This corridor was once used for the Vivarium, an early version of the Aquarium now in our basement. The corridor is now used as a staff walkthrough and for storage.

The bees that lived in the Nature Base are also a feature that has been around a long time, although once upon a time they would produce honey which was eaten by staff.

Up to 2024

Go on a walk through of how the Gallery looked before it closed for refurbishment in March 2024.

The future

We’re so excited to continue the story of this gallery through the Nature + Love project, and Gallery redevelopment.

A love of nature and time spent in natural environments is a value we all share, and a value that has gained greater significance following the pandemic. As London’s only museum of global nature and culture, the Horniman is in a unique position to engage a wider range of people with its heritage collections and the natural world.

We wish to create a Gallery that inspires our visitors to explore and celebrate our love and need for the natural world, instilling a sense of curiosity and wonder and challenging them to take positive action to help preserve the world we all share.