Of course, there are other female firsts at the Horniman we would love to know – who was the first women who worked here?

Unfortunately, historic records relating to other roles are not as well kept as those pertaining to curatorial staff. As our Archivist, Carly Randall, points out, “published staff information focused on curators and not the behind the scenes roles that women would have, historically, had easier access to (e.g. running the shop and tea room, cleaners, educators, casual workers and volunteers etc).”

Do you have any stories about members of your family who worked in the Horniman during our earlier years? Please get in touch with us via web@horniman.ac.uk

Jean Jenkins: Music

Out of the three women we feature, the one we know the most about is Jean Jenkins, who played a key role in the UK’s knowledge of world music. She helped to provide a documentary record of musical traditions that have disappeared or changed beyond recognition during her career.

Jean was born in the Bronx in New York in 1922 into a Jewish family, and had an early interest in folk music. She was a union organiser and civil rights activist, and was part of the folk scene in New York before moving to Missouri, where she studied anthropology and musicology in the 1940s, working for a time in the Ozarks region.

Her letters reveal she was assaulted in Arkansas in the 1940s, and felt harassed by the Ku Klux Klan according to Henrietta Lidchi, Keeper of World Cultures, at National Museums of Scotland. Her decision to emigrate to the UK in 1949 with her first husband, may have been due in part to this harassment and the atmosphere of the McCarthy era of purges; Jean was on the wanted list because of her campaigning work for Black rights in trade unions.

In London, she embarked on a PhD at the University of London, SOAS and in 1954, Jean found a role at the Horniman as a temporary cataloguer, before becoming an Assistant Curator in 1956. In 1960, she became the Horniman’s first Keeper of Musical Instruments.

During her curatorial role, Jean travelled extensively throughout Southern Europe, Asia and Africa. She was interested in not just the instruments, but the musicians, music played and the context of the environment they were played in. Among many other places, she visited Uganda (1966 and 68), Malaysia (1972), Indonesia (1973) Afghanistan (1974) Algeria and Morocco, and Turkey and Syria (1975).

When I first went out to central Asia, I was in fact looking for the origins of a number of Indian instruments. I found some of them of course but that wasn’t at all what interested me about the trip. I went out there and heard a lot of music that I had not heard anything like at all before, and it was my first field trip, and from then on, I heard music which connected up with central Asia. Every single time I have taken a field trip I have heard something which connected up in some way or another.

During these field trips and excursions (some funded out of her own pocket) she collected hundreds of sound recordings, over 1,000 slides and photographs, and also kept regular diaries, which are held at National Museums of Scotland.

In addition, she collected a vast range of musical instruments, many of which are in our collections.

In the early 1970s, as part of the World of Islam Festival, she was commissioned by the Festival Trust to acquire a large collection of musical instruments for an exhibition at the Horniman.

Jean travelled to most of the countries in the world where Islam was or is practiced, as the state religion or which had come under its influence in the past, from Southern Italy to China. She curated the exhibition ‘Music and Musical Instruments for the World of Islam’ which ran from 3 April – 6 October 1976, introducing the collections to a much wider audience.

In 1978, Jean left the Horniman and worked independently in Edinburgh, France and Germany, curating exhibitions like Man and Music in Scotland in 1983.

She died in 1990.

Valerie Vowles: Anthropology

Valerie was the first female curator for our anthropology collections, then known as Ethnographic collections.

We could find very little material about Valerie before her time in Uganda in the 1950s; nothing about her upbringing or early interests and career.

She wrote in the Museum Ethnographers Group journal (October 1981) that when she arrived in Uganda in 1951, a new museum was being built. She collected for the new Uganda Museum, travelling, “for the most part in the northern half of the country, but as time went on I was invited to other areas where people wished to ensure that their way of life was adequately represented in the museum.”

Merrick Posnansky, Curator of the Uganda Museum, wrote,

We were fortunate to have Valerie Vowles, probably the best ethnographer in Africa, maintain the collections immaculately. The storerooms had shelves on rails to maximize space, an innovation only introduced to the United States 20 years later. She had developed a system for periodic inspection of every item, refreshing accession numbers as necessary and sealing artefacts in plastic bags to keep out insects and dust.

Half way through the initial exhibition scheduled following the new museum opening, Valerie suffered a period of doubt about their “audience appeal.” She felt that there was a risk of boring the audience with objects that they used every day in their own homes.

In an effort to understand the interests of young adults she spent a year ‘on and off’ talking to students and professionals to make recommendations back to the museum about content, but the advent of a promotional campaign from Uganda’s new TV service meant that audience interest was no longer a problem and the museum became very popular.

Valerie was an Assistant Curator at the Horniman from 1968 until 1975, before becoming Keeper of Ethography from 1976 until 1982.

In the early 1970s, Valerie had established a solid relationship with Doreen Nteta who was an assistant curator of the recently established National Museum and Art Gallery of Botswana (NMAGB). They started a joint collecting initiative, collaborating on fieldwork to collect very well documented San material which was distributed between the two museums.

Botswana was recently independent (1966) and Nteta was keen that the national museum held a global collection, similar to other world-focused museums, rather than focusing only on southern African material. Nteta was particularly keen on material that spoke to their existing collections. An exchange was agreed between the Horniman and the NMAGB whereby a selection of Australian and Pacific stone tools were sent to Botswana in exchange for further San material.

It was under Valerie’s (and later Keith Nicklin’s) keeperships that the Horniman’s systematic collection of African materials began, after a focus on African visual culture in the past. It was this approach which led to the collections of the everyday material culture of specific African peoples, which is very much in evidence in the World Gallery today.

Valerie also played a key role in the creation of the Museum Ethnographers Group (MEG). Peter Gathercole wrote in 1997, during a reflection of the creation of the group, that by the early 1970s, “many of us working in museum ethnography felt that the subject needed a more self-conscious position in both anthropology and museology in this country and museum ethnographers a better defined role.”

During a meeting in Liverpool in 1974, Valerie and Charles Hunt (from Merseyside County Museum) both “expressed mutual frustration with the existing ethnographic scene.” Following this, Valerie organised a meeting at the Horniman on 22 May 1974 with Hunt as the first speaker. The title of the event was ‘Ethnography in museums: a reassessment,’ and according to Gathercole, “the response was excellent” with “most of the 40 people who had indicated that they would come did so (some 15 are still MEG members).”

Valerie continued in her involvement with MEG in the 1970s, acting as Secretary and Treasurer of the Group in 1976.

After Valerie left the Horniman in 1982, the trail gets difficult to follow again, although we believe she was living in the UK in the early 2000s.

Does anyone know any more about Valerie’s life and career? Get in touch (web@horniman.ac.uk) and we’ll update the blog.

Dr Penny Wheatcroft: Natural History

The final curator we found was Dr Penny Wheatcroft, who was the first female Keeper of Natural History at the Horniman in the early 1980s.

Penny was born in September 1945 and we know that she worked at the Herbert Museum and Art Gallery in Coventry from 1976 until 1980. She joined the Horniman as Keeper in 1980 and was here until 1985.

According to research carried out by the University of the Third Age in 2011, Penny spent a great deal of her time with the day-to-day running of the museum, along with live animal displays of fish, reptiles and bees. She instigated a new catalogue system for the 40-50k specimens which hadn’t been documented since the 1930s, as well as a project to oversee renovation in the present Natural History gallery.

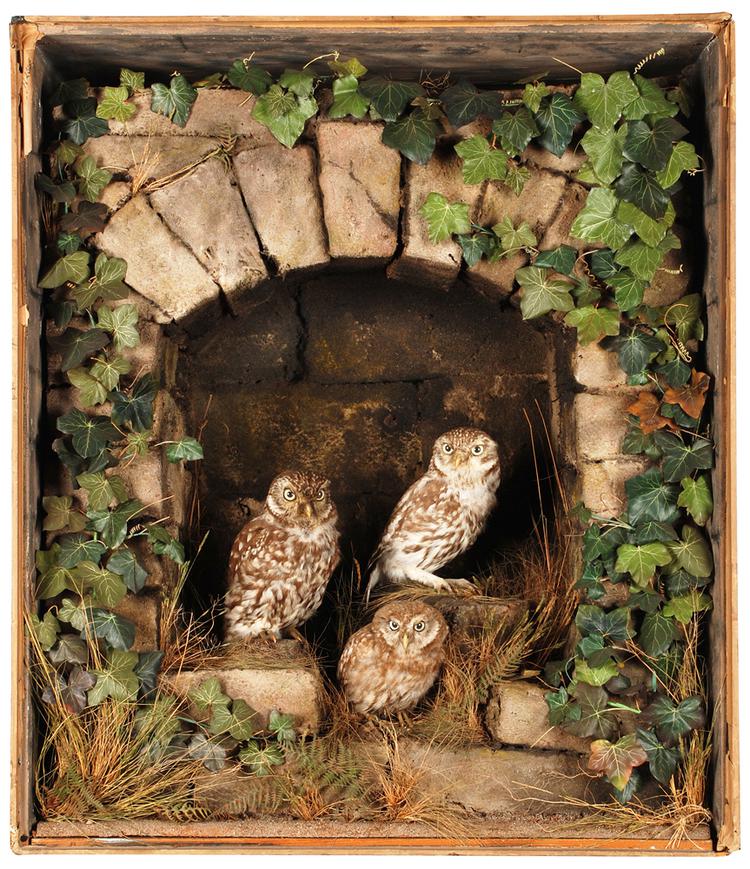

One of the key acquisitions she oversaw was the Hart bird collection, purchased from Stowe School in 1983. These 245 cases of stuffed birds, often in striking dioramas, were created by Edward Hart (other parts of this collection went to Leicester Museum Service and Hampshire County Council Museums Service).

Little Owl

Natural History

Within the sector, Penny was heavily involved with the Biology Curators Group (BCG), which merged with the Natural Sciences Conservation Group (NSCG) in 2003 to form the Natural Sciences Collection Association (NatSCA). She became Secretary of the BCG in 1983.

During her time at the Horniman, our natural history collections unfortunately suffered a series of thefts, vandalism or attempted thefts over what must have been a very stressful month. In a letter to the BCG, Penny wrote,

Recently the Natural History Department at the Horniman Museum gained a new and enthusiastic type of visitor. Unfortunately these keen would-be naturalists were inclined to visit outside the normal opening hours, possibly carrying large sacks labelled SWAG.

She sought help from the group on the subjects of valuation, as she was struggling to convince the “catford cops” of the value that these objects (eggs and taxidermy fish), which could be illegally sold.

Penny believed that these incidents were originated by the same person or group, and warned, “if an anaemic and somewhat scarred individual offers you a cheap carp or some cracked eggs – be warned, it could be our visitor.”

She moved on to the Natural History Museum as an Exhibition Developer in 1985, then known as the British Museum (Natural History), who were not as keen on Penny’s involvement with the BCG (as noted in the groups’ newsletter in 1987). She stepped down formally from the group in 1986.

Penny was involved in the trade union at the museum, and campaigned to “maintain free enquiry and research facilities” at the museum, as well as campaigning against entry charges. According to another newsletter from the BCG, she was “fighting that policy tooth and nail.”

From 1989, she moved within the newly renamed Natural History Museum to become Information Officer in the Visitor Resources Section, and was the Branch Chair of the of the Institution of Professionals, Managers and Specialists. Comments from Penny appear in The Times twice in 1990, emphasising her role within the union.

First, a letter to the Editor about an article focused on changes being implemented by a new Director at the museum. She wrote,

Your leader of April 27 falls into the classic “king's new clothes” trap, assuming that any glossily presented change is necessarily for the good. Its insidious sub-text is that the new Director of the Natural History Museum, Dr Chalmers, is valiantly battling against a fusty horde of ‘curators of the old school’. Nothing could be further from the truth. The museum's importance as an international centre of excellence in taxonomy and mineralogy continues in the face of inadequate Government funding and managerial hostility.

The very next day, she was quoted in an article about consulting with the union before committing to job cuts, claiming a victory ahead of planned strike action.

After this, the trail becomes cold, although we believe she died in 2010.

Does anyone have any more information about Penny and her career? Get in touch (web@horniman.ac.uk) and we’ll update the blog.

With thanks to Carly Randall, Archivist, and Johanna Zetterstrom-Sharp, Deputy-Keeper of Anthropology.