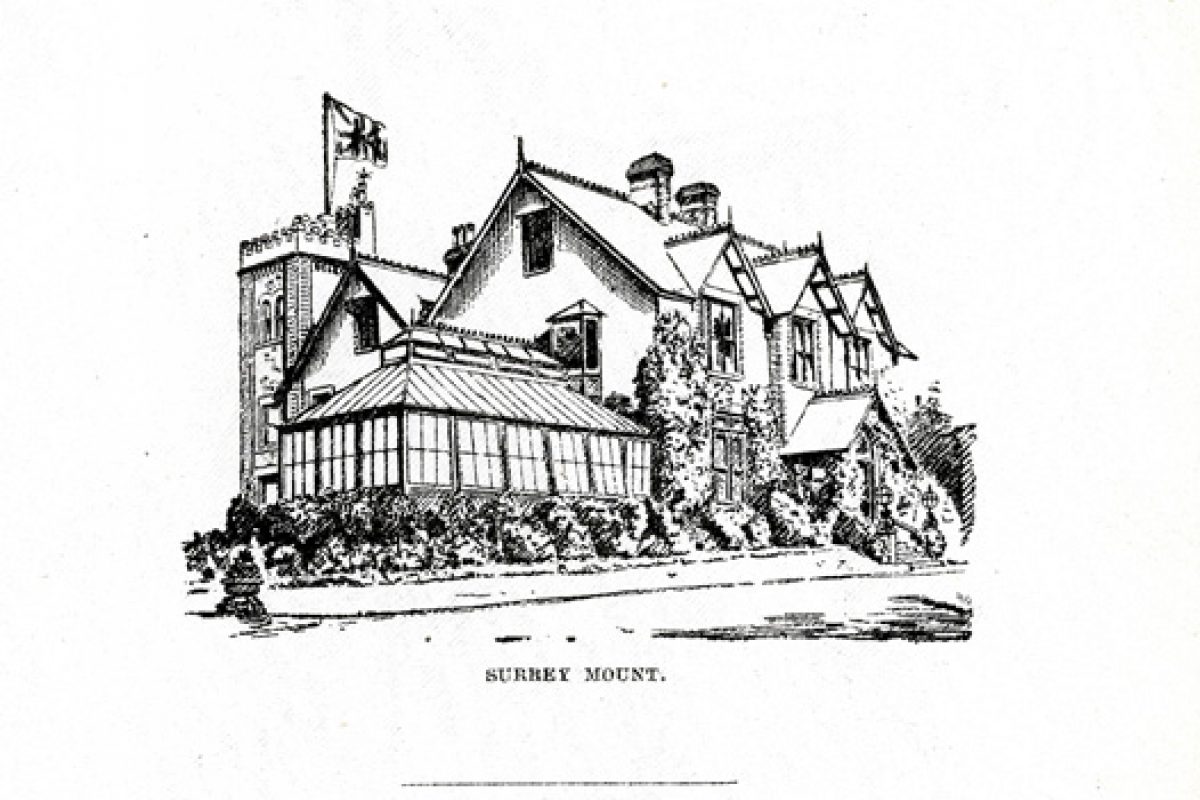

The two wed on the 16 November 1886 at St George’s, Hanover Square, held their reception at the family home Surrey Mount, and led the wedding party in an “inspection” of Surrey House Museum which was the original site of the Horniman.

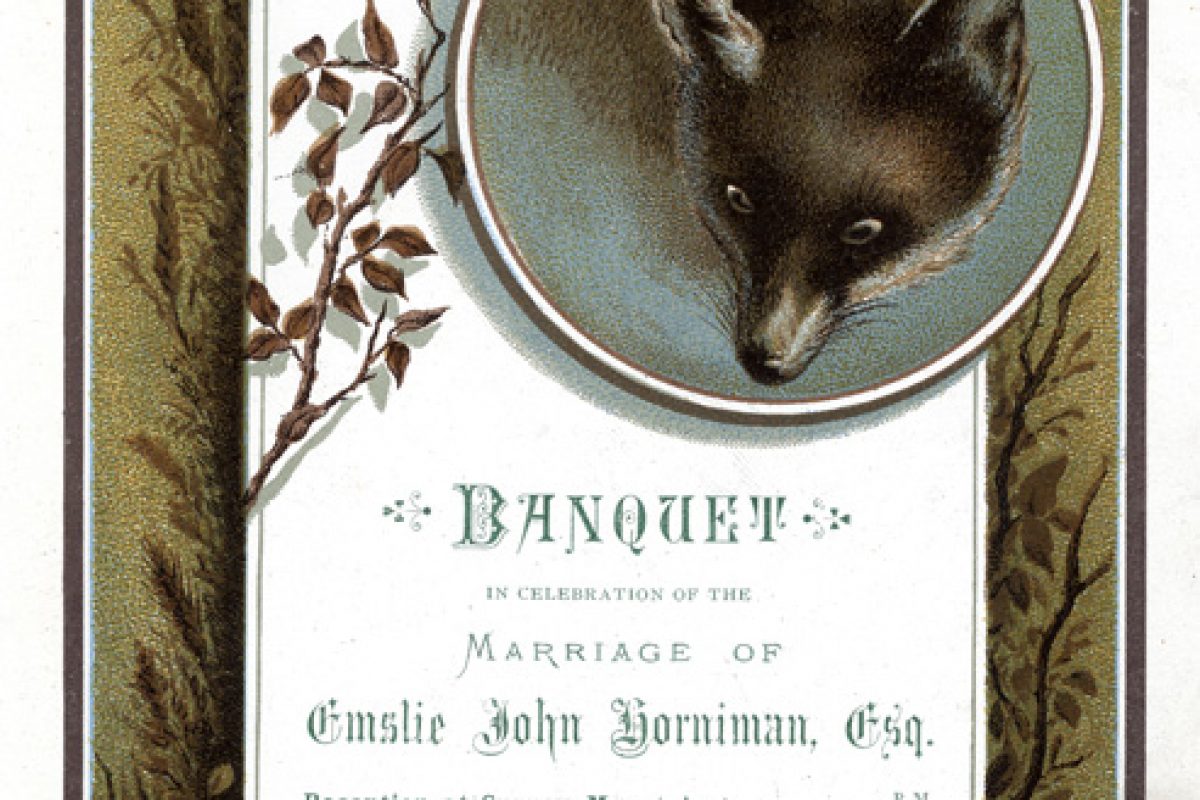

We recently unearthed a scrapbook in our Archives containing photographs, press cuttings and other souvenirs recording the earliest years of the Horniman. One of the highlights of the scrapbook is a beautiful wedding programme printed for guests attending Emslie and Laura’s wedding celebrations. The programme gives us a wonderful look at how wealthy Victorian families celebrated their nuptials.

What is especially fascinating about this piece of Horniman history is that this wedding almost never happened at all.

Emslie Horniman was born in 1863, the second child of Frederick John Horniman and Rebekah Horniman. He studied at the Slade School of Art with dreams of becoming an artist, before later taking up a career in politics and philanthropy.

Laura Plomer was the daughter of Colonel Arthur Plomer. Our historic visitors’ books show that Laura and her family were frequent visitors to the Horniman in the early 1880s. It was there she socialised with Emslie and his older sister Annie.

In his autobiography, Double Lives (published in 1944), Laura’s nephew William Plomer describes how Laura’s family disapproved of her relationship with Emslie. According to William, Laura’s parents thought of Emslie as ‘an atheist and a radical’ and considered the Horniman family to be of inadequate social status despite their extensive wealth and connections.

His autobiography goes on to tell us that Laura’s parents went so far as to lock their daughter in her room in the hope that she would ‘come to her senses’ and end their relationship. Not so easily thwarted, Laura decided to stay in contact with Emslie by letter. But there was one problem: her parents had cut her off from their money and she had no access to postage stamps.

Still determined, Laura used the one asset at her disposal: her magnificent head of fair hair. After cutting off a generous lock of her own hair, she escaped her home to sell it to a Mayfair wigmaker and used the payment to purchase stamps.

Realising their daughter would not bend to their wishes, Colonel Plomer and his wife finally consented to her union with Emslie. William Plomer writes that ‘[Laura] went off with a new name to a new life with her radical aesthete, and enjoyed, for the next half-century or so, health, wealth and much happiness’.

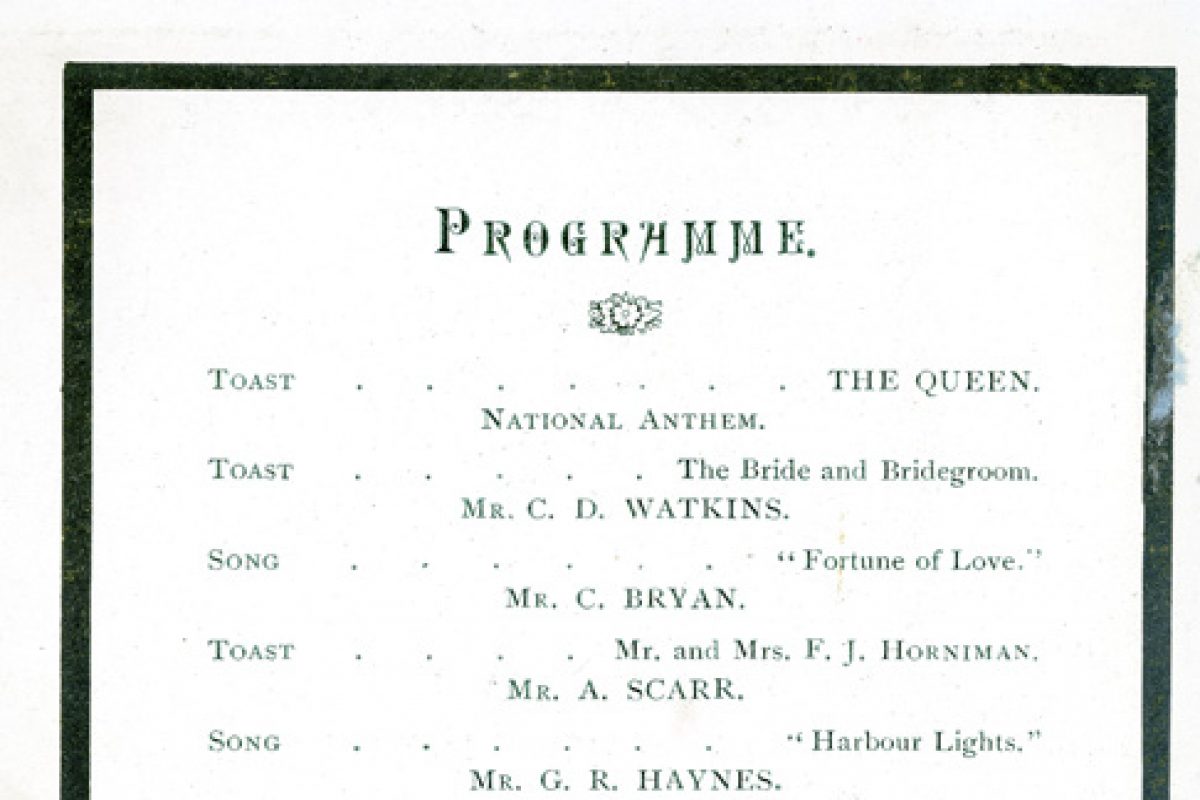

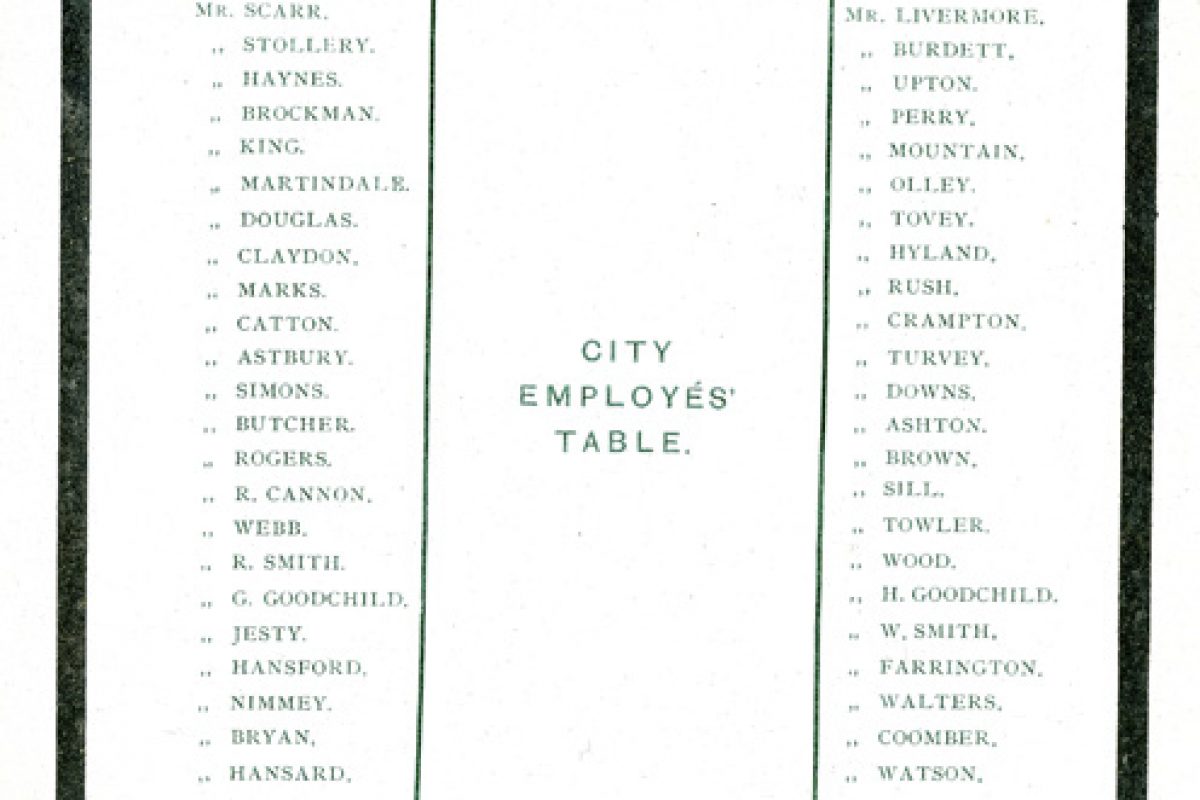

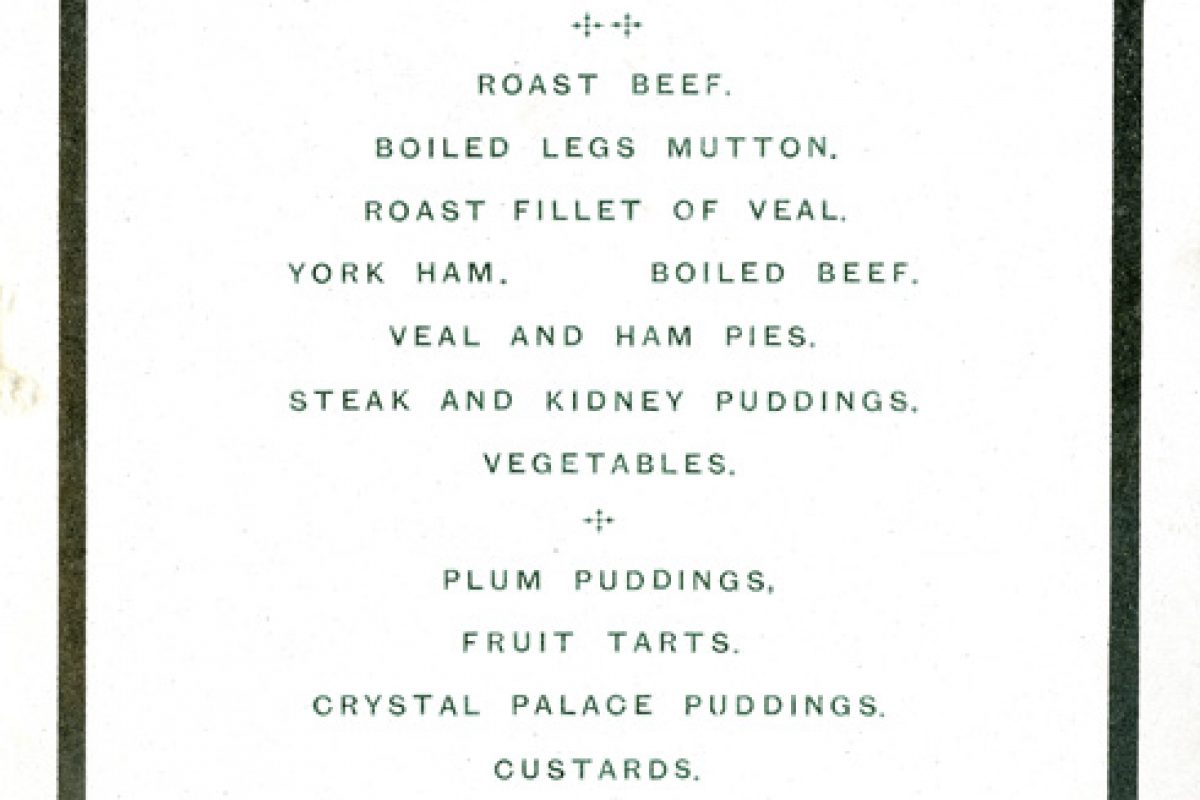

Laura and Emslie’s wedding programme, which survives in our Archive collection, lists the toasts and speeches made in honour of the happy couple. Also featured is a seating plan and a menu boasting delights such as ‘York Ham’ and ‘Crystal Palace puddings’.

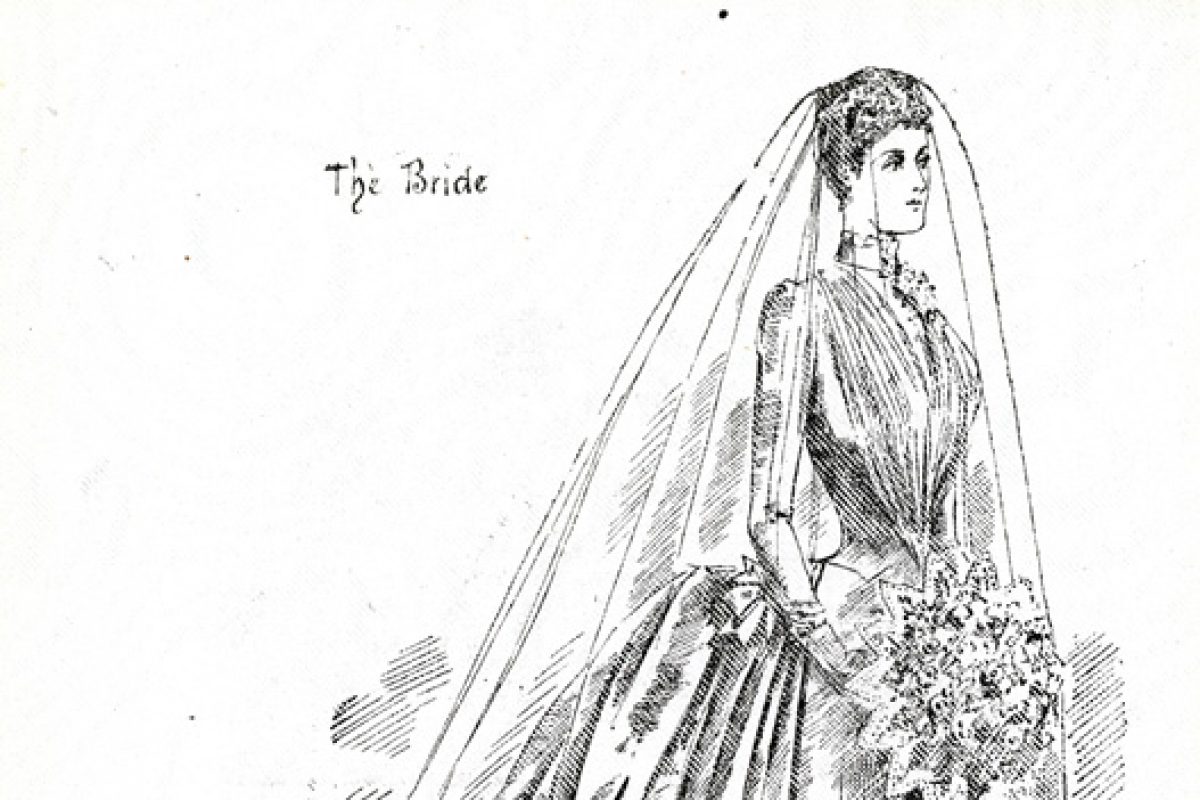

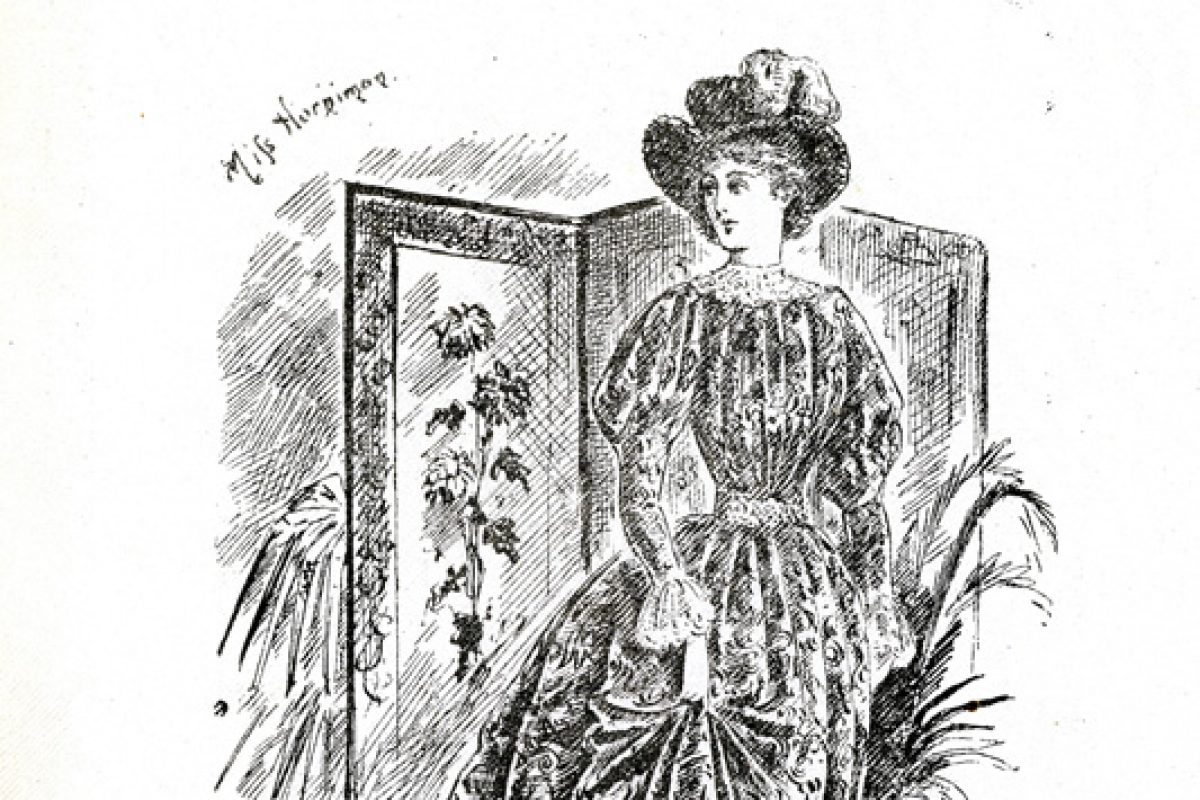

The programme contains extraordinary sketches and meticulous descriptions of the bride’s dress and veil, which she fastened with diamond stars gifted to her by Emslie’s mother. Alongside this is a sketch of the dress worn by Emslie’s sister Annie, which Emslie had designed especially for her.

These celebrations were likely the first time the Horniman had hosted a wedding, but they were certainly not the last. Frederick Horniman’s great, great, great-granddaughter Hilary married in the Horniman’s Conservatory in 2014 and the Museum and Gardens are still a popular wedding venue to this day.