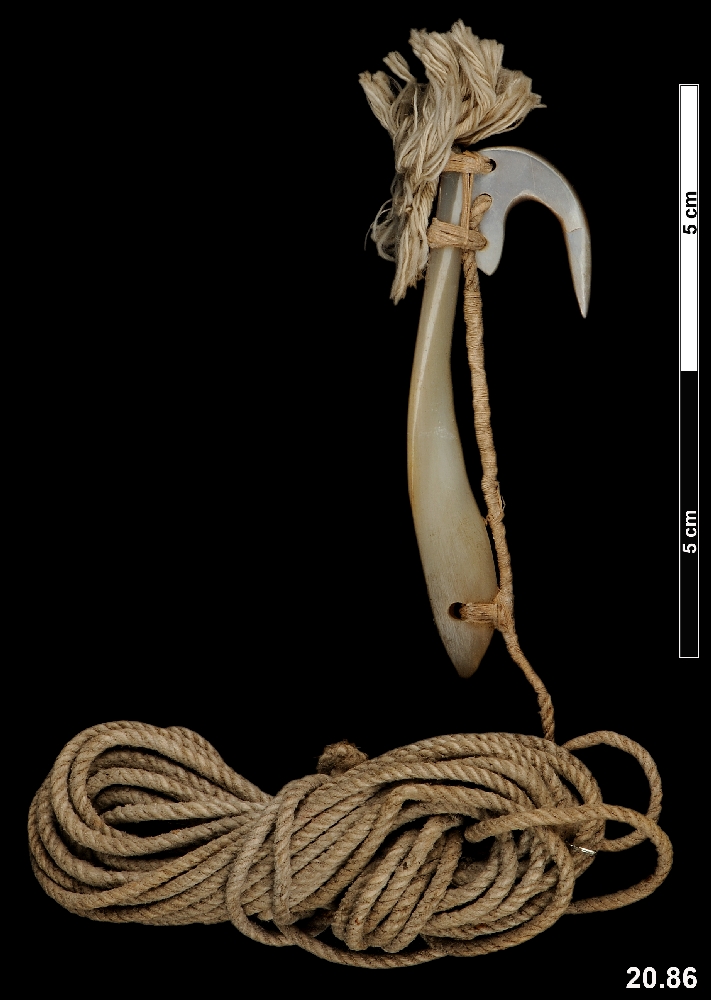

Shell fish hook made from two pieces with the hook part made from shell that is pale on one side and dark on the other. The hook has three holes on one side which has string threaded through binding it to the rest of the shell.

Trolling Fish Hook, Matau, Society Islands, Central Polynesia. This little masterpiece reflects the pains that fishermen from Tahiti and the smaller Society Islands took to improve their chances of success. This is a trolling hook. Trolling hooks are intended to be pulled through the upper water below the surface (either by trailing them behind a moving boat, or drawing them in on a long line); all trolling hooks combine both lure and hook into one hunting tool, and all are intended to be mistaken for a small fish by a larger, predatory pelagic fish of the open, upper ocean. Society Islands hooks of this kind were predominantly designed for catching bonito tuna (Sarda spp.). The hook is composed of three parts: First, the long central shank of iridescent white pearlshell (Pinctada maxima) is cut into a fish-shaped profile and has a drilled eye-hole; in this way, it combines the qualities of both Western plug lures and spoon lures. Second, the barbed hook is similarly cut from the black section of a black-lipped pearlshell (Pinctada margaritifera var. Cumingi), the shell which produces French Polynesia’s famous black pearls. Third, these two components were each tied independently to the strong coconut-fibre line (aiha), and then tied together. This practice of doubly tying the parts together was a distinctive feature of Polynesian trolling hooks, and meant the fisherman had a greater chance of retrieving one or both shell pieces if the hook began to break up. It is no exaggeration to describe the Tahitian manufacture and use of trolling hooks as both an art and a science; men had an encyclopaedic knowledge of almost imperceptible differences in the colour, shape and shine of the various pearl oysters feeding off different beaches on certain islands, and they collected these different shells to make and meticulously polish numerous different shanks and hooks. Men kept these hook parts as the collecting work of a lifetime hidden in barkcloth tool pouches which they took out with them in their boats. Sitting on the sea, the fisherman would assess the time of day and tide, amount of cloud-cover and blueness of the daylight, surface conditions of the water, and local currents, to select the most efficient combination of shank and hook from his repertoire for the precise conditions he found himself in. As a result of this attention to detail, the Tahitian fisherman’s success was almost legendary. Pearlshell, black pearlshell, coconut fibre. Later 19th Century. Formerly in the private collection of Sir Everard Im Thurn.