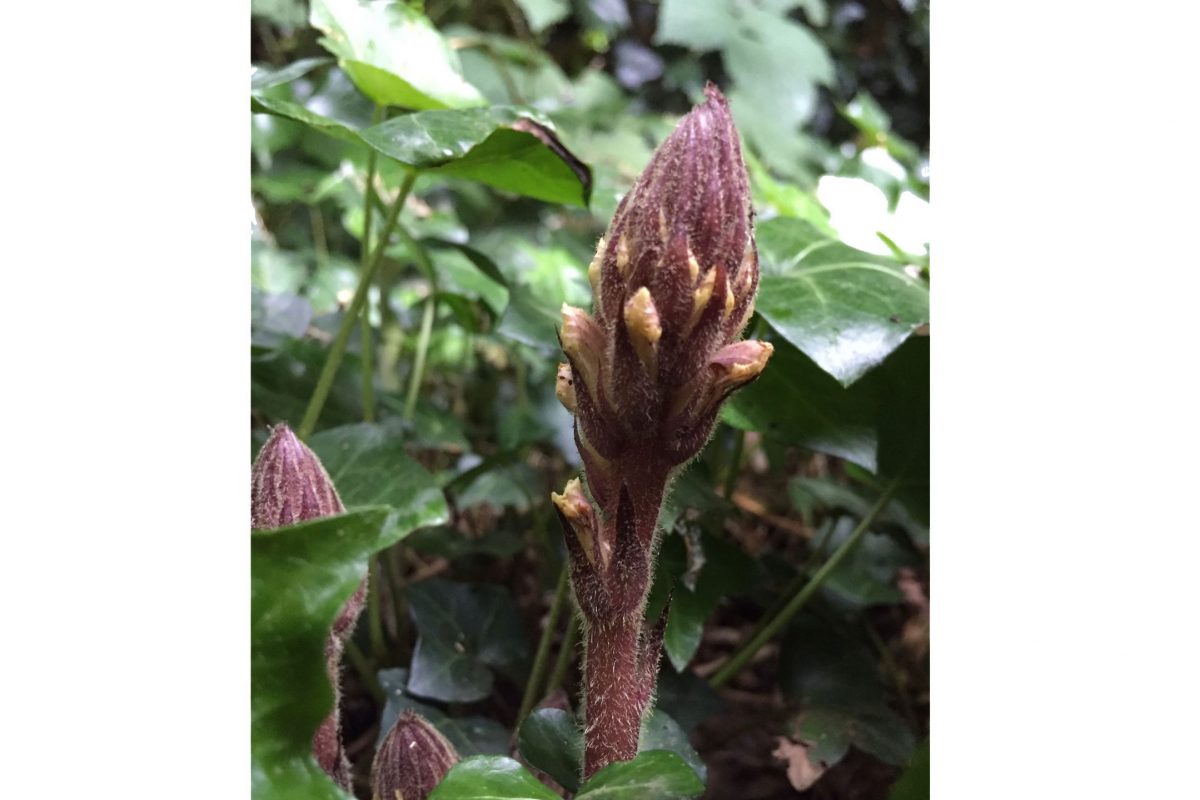

One summer morning last year, right at the start of the trail, as I was packing an unnecessary jumper into an unnecessary backpack, my daughter called me as she had spotted these strange and beautiful things periscoping up through the ivy.

A quick flick through the flower book told us that they were Ivy Broomrape (Orobranche hedera) – although the book made it much more complicated than it needed to be.

Flower books do not like it when you can identify something easily by just looking at the picture, they want to spoil your fun by insisting you measure the length of the episepals, and look for tiny greyish hairs just underneath some structure you never heard of.

But we ignored the botanical killjoys and turned our attention to this remarkable plant.

There is much talk at the moment about the so-called “Wood Wide Web” and the intimate and mysterious chemical communications between tree roots and mycorrhizal fungi. Wherever you look in the non-human world there are equally incredible and fascinating relationships between different species, such as the relationship between broomrape and ivy.

The broomrapes are “classic” parasites, they offer nothing useful (that we yet know of) to the ivy, but they steal the food they need from its roots. They are thus ‘obligate’ parasites, meaning that the broomrape cannot survive without its host plant, ivy.

It takes water, nutrients, and, most importantly, sugars, which provide the energy for the chemical reactions which power all living things. As we may remember from our school biology lessons, plants get their sugar from sunlight and carbon dioxide, with the catalyst chlorophyll making the chemical reaction happen. Chlorophyll is what makes most plants green.

But there is not a shred of green on the strange purplish-brown and yellow broomrape. Why make sugar if you can steal it from someone else?

Broomrape seeds lie in the soil often for many years before germinating.

The host plant – ivy – produces chemicals which the seed is able to detect. If there is a sufficient concentration of the chemical in the soil, the seeds become seedlings, and put out tiny root-like growths that attach to and penetrate the roots of the ivy. A swelling or node develops at the point the seedling is attached to the ivy and this gave rise to term ‘rape’, which apparently was an old word for turnip.

Using the nourishment from the ivy, the flower spike grows and produces its wonderful orchid-like spires: dull cream flowers poking out from the reddish leaf scales.

These attract bees and other insect pollinators, so cross-fertilisation between plants can occur. Seeds form, fall to the ground, and the cycle starts again.

Ivy broomrape is not that common.

If you look at the Biological Records Centre online atlas of British and Irish flora you will see it is mainly a southern English and Irish plant. There are concentrations along the south coast of England and the Channel Islands but hardly any records north of the Midlands.

It is thought this distribution reflects that the original ‘native’ plants had evolved to parasitise a particular sub-species of ivy (Hedera helix hibernica) which is found mainly along southern coastal cliffs, undercliffs and hedge banks.

Gardeners, fascinated by this curious plant, cultivated it and so it spread from its original distribution. The London population is therefore probably introduced. So, like the alkanet and the winter heliotrope, this is another wonderful Horniman plant brought to us courtesy of the gardeners of the past. It doesn’t seem to be doing any harm on the trail, which certainly is not short of ivy!

Please go and have a look, it is all along the trail at the path edge and merits a close peer. The spikes are at their best now but will last through the winter, becoming drier and browner.

Some people don’t like ivy, seeing as it as boring and dominant in many of our woodlands. I must admit to thinking that too sometimes. But ivy has a crucial role in feeding our insects in autumn, providing nest sites for birds and as a winter hibernation zone for smaller animals.

And it supports the magnificent ivy broomrape.

Sometimes we have to prune back ivy when it is smothering a precious tree in its attempts to reach the sun, but let’s do so with respect and care for this important part of our ecosystem.

Another rather dashing occupant of the trail is this splendid creature – the black and yellow longhorn beetle (Rutpela maculata).

Unlike most insects, this is one you can identify quite easily.

Its dramatic markings are a form of mimicry; evolution has made it look a bit like a stinging wasp so predators will leave it alone. You will see these flying around hawthorn and brambles during their few week adult life, during which they feed on pollen and nectar, mate, and lay their eggs in dead wood.

I think after that they deserve their short time in the sun!

Note

If you want a good simple and clear wildflower guide, after trying a few I think by far the best for beginners is this one, which is easy to flick through with excellent photos.

Harrap’s Wild Flowers. A Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain and Ireland. Bloomsbury, 2013.