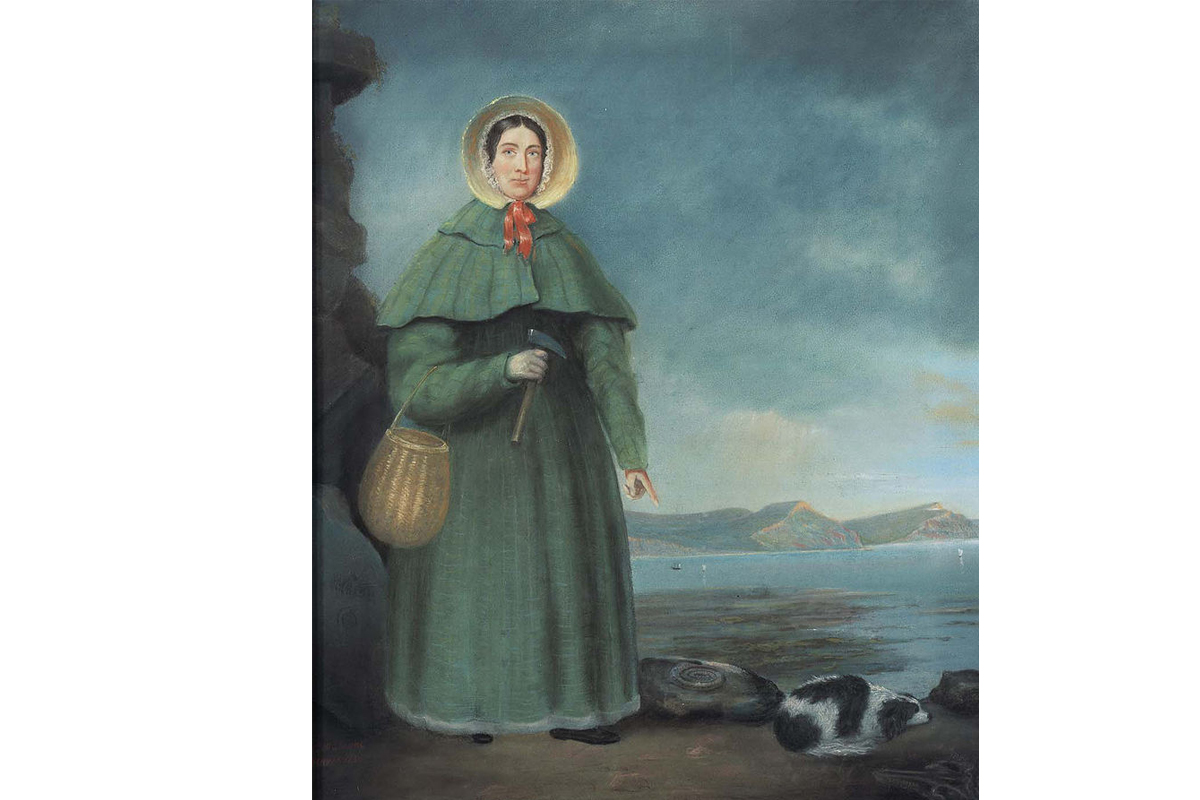

In case you haven’t already heard, there is a very exciting film called Ammonite based on the life of fossil hunting heavy weight Mary Anning (1799 – 1847).

Mary is played by Hollywood superstar Kate Winslet, catapulting this underrated titan onto the Big Screen (or whatever size your tv/laptop is, given all the cinemas are shut) with the clout of Hollywood royalty.

If you know a few famous historical scientists here and there yet have never heard of Mary Anning, this is not surprising: the most repeated fact about her is that she was barely recognised for her incredible achievements during her lifetime.

Setting the record straight about her achievements has only recently been gaining traction in mainstream channels. She is responsible for finding numerous fossils of global importance, could well be described as the mother of palaeontology, and was a fiercely intelligent woman stifled by the idiocy of systemic gender inequality and prejudice.

The society

Mary was a woman, and a poor woman at that.

Sadly, in Georgian and Victorian England, both women and the working class were excluded from the scientific community and in Mary’s case – from the Geological Society. This Society didn’t allow their first female member until 1904, and their first female Fellow until 21 May 1919. I wonder if it’s coincidence that the latter would have been Mary Anning’s 120th birthday?

Fellowship of the Geological Society may not (or may?!) be high on your own list of priorities but in Mary’s time, recognition by the society meant the ability to publish on scientific discoveries in the field of palaeontology.

So for her, it was a big deal.

Instead, Mary had to let others (men) publish on the specimens she found and take credit for her scientific discoveries and accomplishments. Of which, there were many! The Natural History Museum in London is the custodian of many of her most important fossil finds and their dedicated Mary Anning page bears the rather lovely description, “her lifetime was a constellation of firsts”.

The reptiles

Mary lived in Lyme Regis. It is one of the best-known focal points of a World Heritage Site known as the Jurassic Coast, named for – and protected due – to the plethora of the often scientific game changing fossils that have been found there.

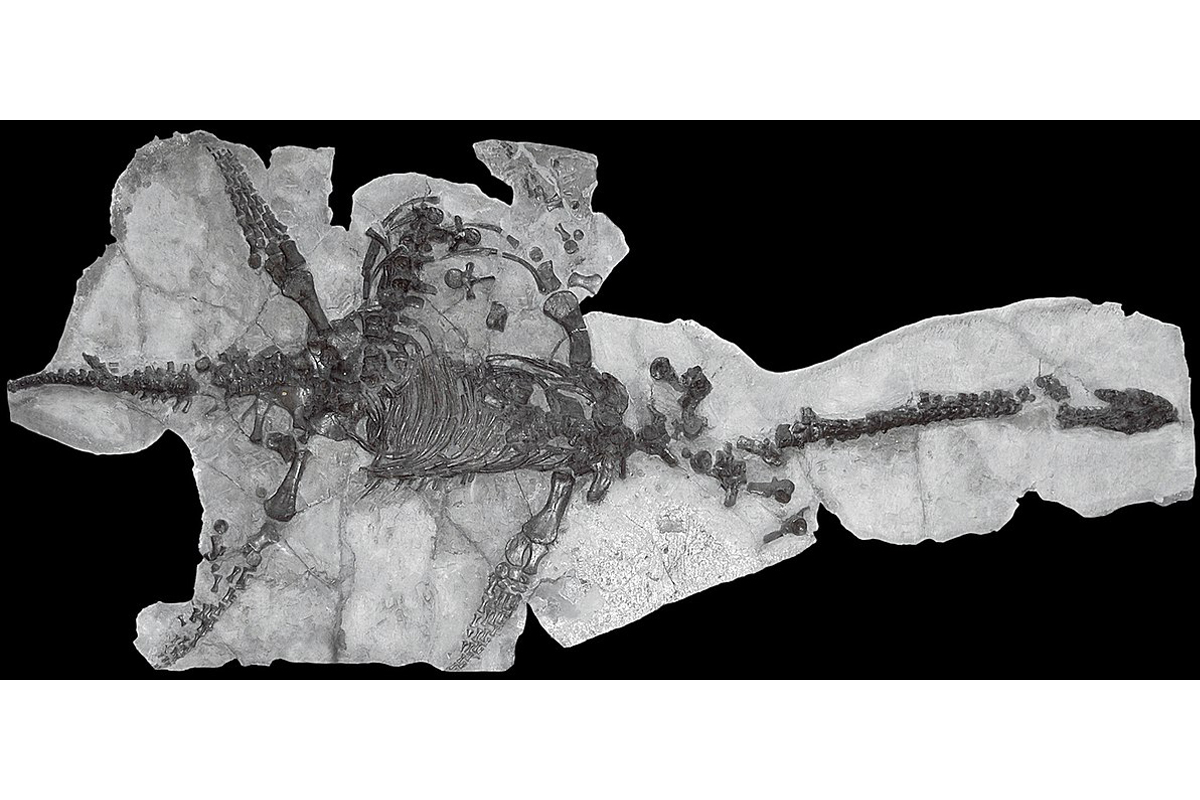

It is most famous for marine reptiles such as the long-necked plesiosaurs and the dolphin-esque ichthyosaurs, and Mary Anning is known to have found the first complete specimen of both, as well as the first ichthyosaur brought to the attention of science*. Both are now hanging in the marine reptile gallery in the Natural History Museum, in London.

Since Mary’s time, countless more marine reptile specimens have been uncovered along the Jurassic Coast, and in her hometown of Lyme Regis. Ichthyosaurs were one of the first animals used to solidify the idea of extinct creatures with no modern equivalent – an idea at the very core of palaeontology, a word that literally means, “the study of ancient life”.

Today, you can walk past many of the ancient marine reptiles Mary discovered which adorn the walls of the Marine Reptile Gallery in the Natural History Museum. It’s often difficult to walk through unimpeded, much like the dinosaur gallery, for all the people standing marvelling at these saurian icons of ancient seas.

At the Horniman, we have a number of marine reptile specimens, probably not collected by Mary (though technically I should say that’s inconclusive!). The specimen below is the snout of an ichthyosaur, found in Mary’s hometown of Lyme Regis. The two long straight bones are the upper and lower jaws, and the numerous fish-frightening pointy bits in between are the teeth.

The tip of the snout is on the left and the braincase would have been on the right, had it been preserved. As you can see, much of the skull and even the tips of the jaws are missing.

A second partial ichthyosaur skull shows a bit more bone, but was evidently a bit of a mystery to past curators.

As with the specimen above, the skull came to the Museum in the late 1980s as one of the not insignificant tally of ca. 175,000 fossil specimens that make up the Bennett Collection. Although collected (or potentially purchased) by Walter Hellyer Bennett (1892-1971) who was a professional geologist, by the time it arrived at the Horniman the specimen was without written data or identifying paperwork. In 1996, it was described as a ‘fossil fish jaw’ – ichthyosaurs are reptiles, not fish.

Amazingly this doesn’t seem to have been corrected until 2013, when a visiting scientist recognised it as an ichthyosaur. In fairness to the lad or lady in 1996, ichthyosaur means ‘fish lizard’ due to the not insignificant number of similarities ichthyosaurs have with both fish and reptiles.

The specimen’s record in the Horniman database lists it as a cast, but just this week closer inspection of the specimen revealed it to be genuine fossil.

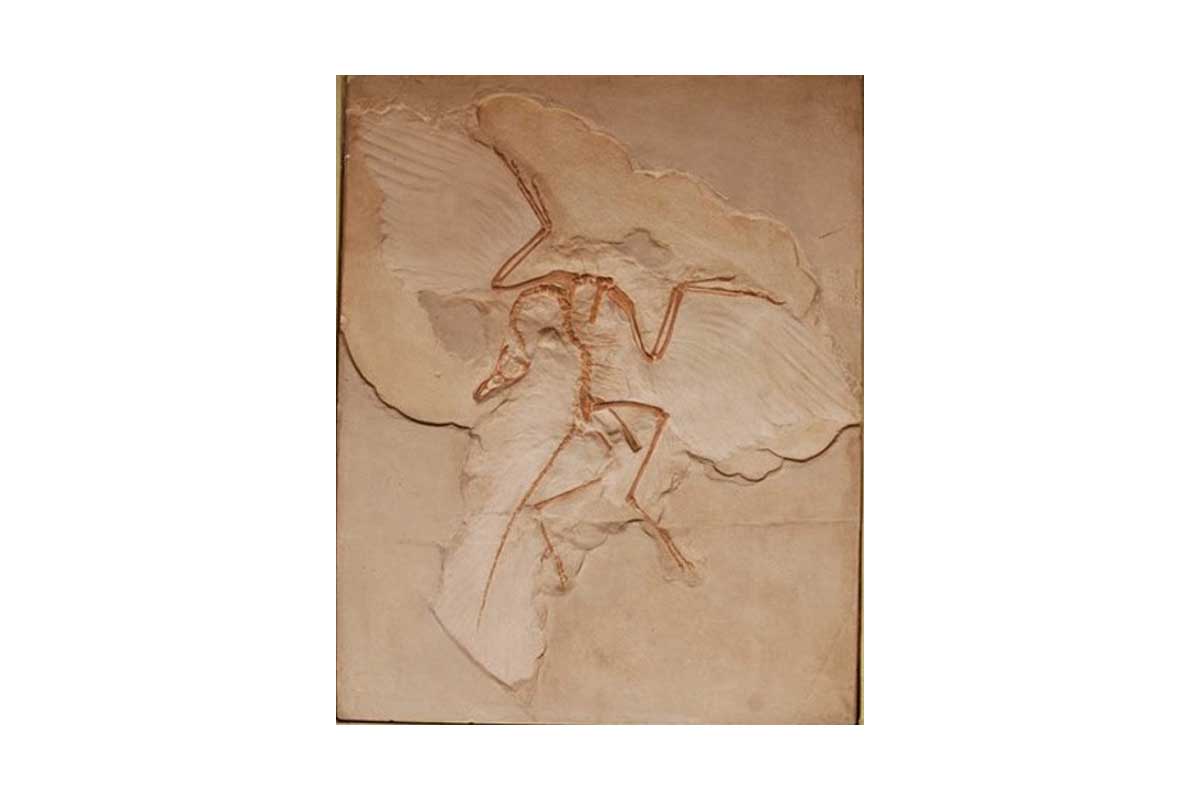

Casts of fossils are extremely important for lots of reasons. They often capture enough detail that researchers can study the cast instead of the fossil, particularly important for very rare specimens (such as the famous, game-changing, Archaeopteryx, see below) or ones that are super popular like every Tyrannosaurus ever found. Casts are also often historical objects of importance in their own right.

The plaster cast of Dippy the Diplodocus, first unveiled in 1905 and which graced the main hall of the Natural History Museum in London from the 1970s until 2017, is a much-loved icon of the institution and a precious specimen all of its own. Yet it is actually just one of several casts of the original Diplodocus specimen, which is held in the collections at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, USA.

So being ‘just a cast’ is by no means a shameful past-time, but being re-identified as a genuine fossil is always an exciting day for everyone.

I suspect the reason our ichthyosaur specimen was initially thought to be a cast is because where the wood of the lower part of the frame has come away slightly, you can see a cross-section of the matrix (the fancy scientific term for the rock in which a fossil is found) and it very much looks like plaster, not rock.

The reason it looks like plaster, is because that’s what it is. A common past time in the Victorian era especially was to excavate a fossil, knock off the surrounding rock, pop it into a wooden frame and then infill the gaps with plaster, subsequently painted to look like rock.

If you look closely at the image of the ichthyosaur specimen above, there is an area of matrix where the eye socket and braincase would have been (in the top right) that is a slightly paler grey than everywhere else. This is genuine rock, and the bone is genuine fossil. But all of the surrounding, darker grey “rock” is indeed plaster.

Many of the fossils in Mary’s time would have been treated in this way, presumably to make them more presentable display pieces. Indeed many of the historical specimens in the Natural History Museums’ Marine Reptile Gallery, or in the collections of the Sedgwick Museum in Cambridge, are either partially or wholly embedded in plaster.

The legacy

Although Mary was well-known, and her skills acknowledged to varying degrees by the academics of her day, she suffered a lifetime of being shunned and overlooked in terms of her scientific standing.

Followed by a further 150 years of no one really correcting the injustice, Mary’s name finally seems to be taking its place in the history books, alongside the plethora of male scientists who published without her name, on the fossil specimens she found.

There are many reasons for Mary’s story gaining momentum. Individuals and institutions alike are working hard to identify imbalances and readdress systemic prejudices against gender, race, sexual orientation and disabilities. There has been a general awakening of society to the idea that we as museums aren’t telling the full story, an inexcusable oversight. Here at the Horniman, we are working hard to address this through our reimagining of exhibits, production of online content, and our Museum-wide colonial legacy programme.

In a recent interview, Kate Winslet (who, if you’ve forgotten the beginning of this article, it was a long time ago, plays Mary Anning in the film) said one of the things she hopes Ammonite will achieve is the inspiration of budding palaeontologists, and in particular ones that don’t fit the stereotypical image (cue Alan Grant).

For starters, the film has a romantic subplot between Mary and another palaeontologist called Charlotte Murchison. There is no known evidence to suggest that Mary was a lesbian, however, there is also no known evidence that Mary wasn’t. So who’s to say! Ammonite is a Hollywood film loosely based on the life of Mary Anning, and no more claims to be an historical documentary than Jurassic Park was a commentary on the forefront of realistic scientific endeavour.

But representation matters, so whether the romantic subplot is fictitious or not, my personal view is that it is a positive move, and I can’t wait to see the film, in all its fossily glory!

* Her brother Joseph found the skull of the first known ichthyosaur in 1811, and Mary later unearthed more of the post-cranial skeleton.