The first aquatic animals in artificial habitats

For millennia, humans have caught wild fish with nets in pursuit of food. Many pre-modern societies also practiced aquaculture; managing captive stock in hand-cut ponds and pools.

Keeping fish for pleasure rather than nourishment has its origins in ancient Korea, China, and Japan. There, ornamental varieties from the adaptable carp family were cherished and displayed in ceramic bowls.

The first Europeans to enjoy fish as a spectacle watched them swimming in tidal pools and the marble tanks of imperial Roman villas (Brunner, 2011). By the seventeenth century, the fish-keeping culture of East Asia had reached Britain. Diarist Samuel Pepys was shown “fishes kept in a glass of water, that will live so forever.” (Pepys, 1665)

It seems Pepys was gazing directly at imported paradise fish.

A century later, most people could still only see and enjoy fish from above when staring down at them in opaque bowls or zoological garden ponds.

In the nineteenth century, growing scientific curiosity encouraged a search for a new perspective on life underwater. A glass-fronted aquarium, stocked with a balance of plants and animals proved to be the answer. The age of the see-through river and the boxed-up ocean had arrived.

Visit the Horniman Aquarium

Why put fish in a glass box?

Before the development of the glazed tank, zoologists would use bell jars, sweet jars, vases, and drinking glasses to study aquatic life.

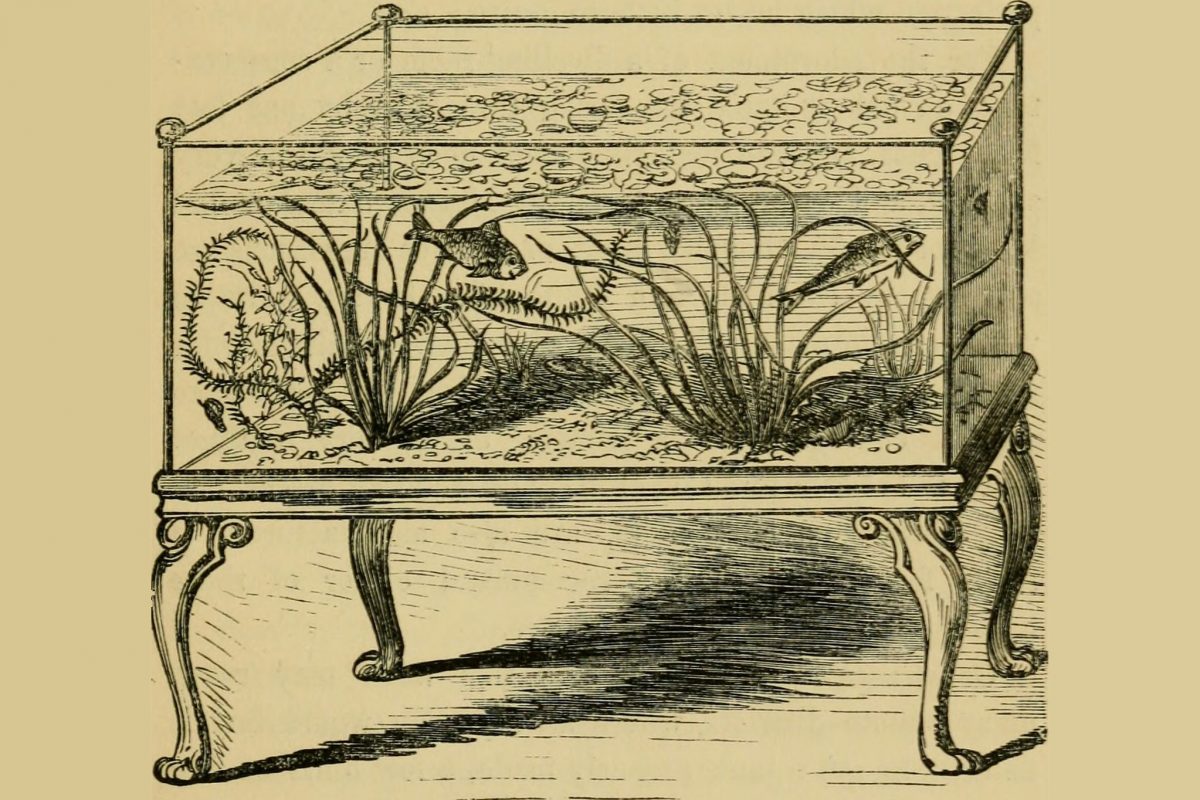

Superior to any bowl or vase is an oblong container made of flat glass. This is because its exposing sides afforded ‘lateral viewing’ and an undistorted, underwater view of an entire aquatic community – freshwater or marine. The interaction of plants, fishes and invertebrates could now be seen and recorded in detail. And no one need get wet.

Marine zoologist Philip H. Gosse (1810-1880) popularised the well-maintained rectangular glass vessel and coined the modern term aquarium.

One of his first tanks measured 2ft x 1ft x 1ft and held 20 gallons of water. It had glass panes secured with putty and wood beading, and a slate base covered in clay, sand, and rock. Suspended above the tank was an aeration unit, dripping two gallons of salt water into it each day.

The development of the early marine tank

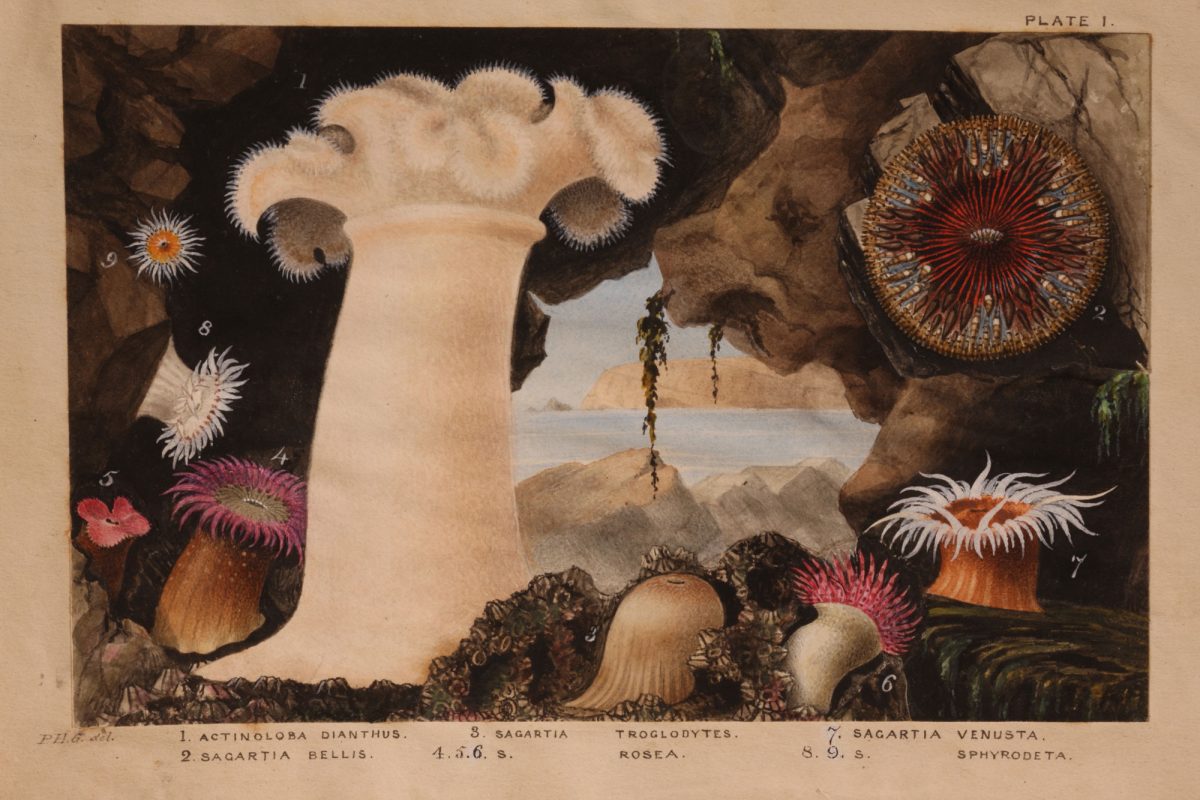

Gosse spent many years trying to understand the interplay of animals, plants, and photosynthesis in a captive saltwater community. He was not alone in his search for such “visible knowledge” (Golinsky, 2005 p.95), other pragmatic collectors and scientists were hard at work too.

As early as the 1820s, biologist Sir John Dalyell (1775-1851) was refreshing the seawater in his sea-anemone containers each day, keeping them alive for many years.

Zoologist Jeanne Villepreux-Power (1794-1871) put her ocean specimens into wooden boxes that relied on a system of hoses to refresh the water. Direct inspiration for the aquarium as a regulated environment came from the sealed growing containers devised by amateur botanist Dr. Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward (1791-1868). These glass cases had first been used to transport plants across what was the British Empire.

In 1852, Pharmacist Robert Warrington (1807-1867) and Gosse simultaneously published their independent findings on the biochemical exchanges between aquarium plants and animals living together in equilibrium (Brock, 1991).

Combining experiment, calculation, and experience, aquarium pioneers devised an apparatus giving them a condensed recreation of a rock pool or seabed floor. The glass-sided microcosm and life-support system had arrived.

What was Aquarium Mania?

Increased leisure resulted in many aspiring Victorian families taking nature into their homes for fun and self-improvement.

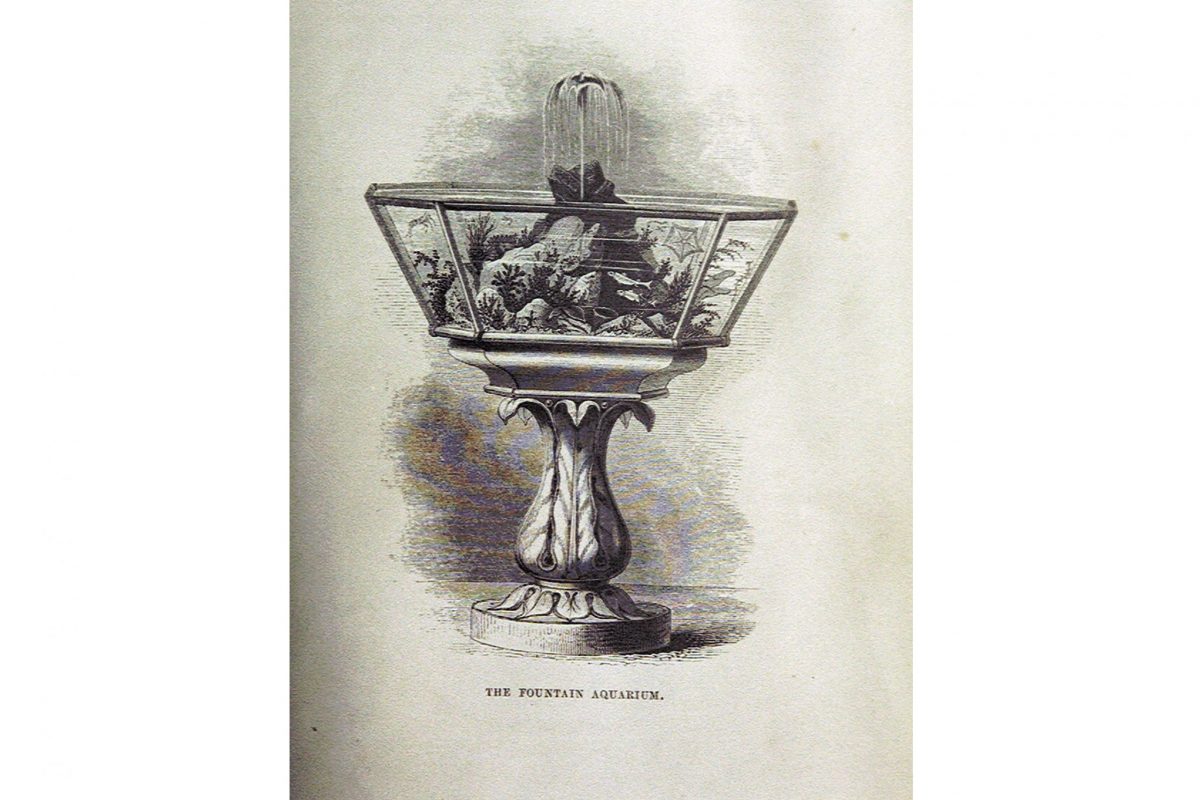

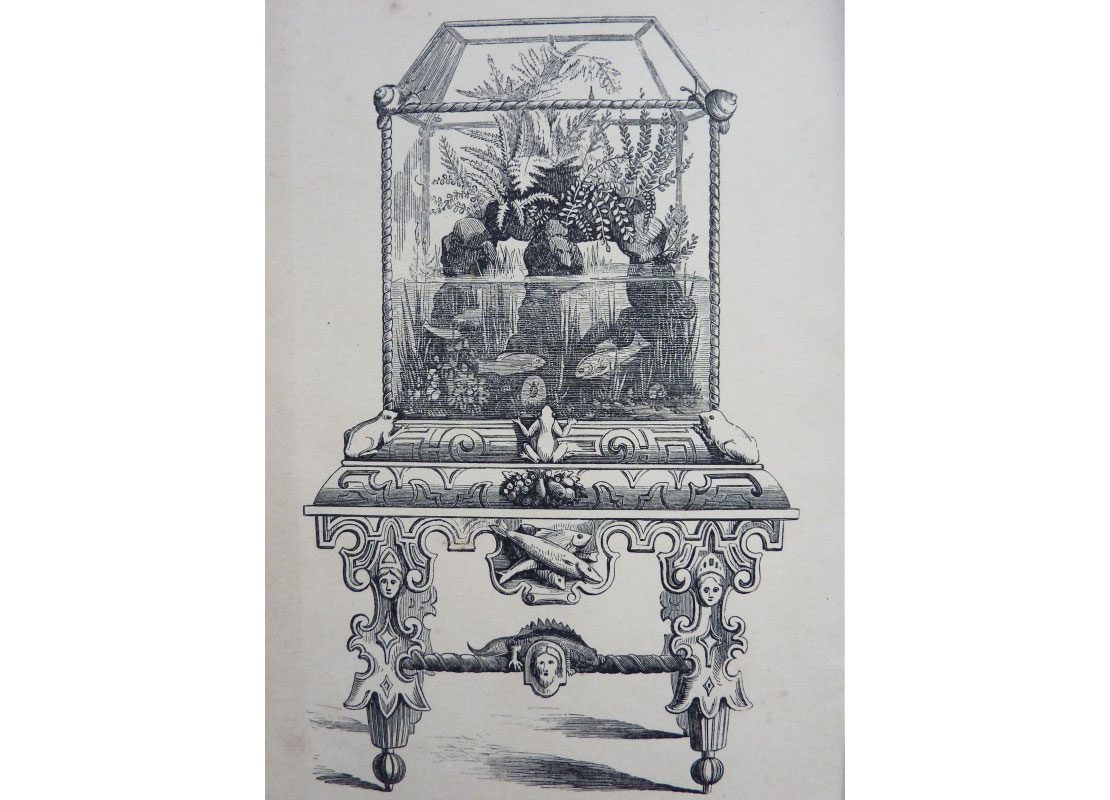

The glass aquarium, in particular, captured the imagination of the British public and led to a short-lived excitement for glazed domestic centerpieces.

A complete aquarium mania ran through the country…shops were opened for the simple purpose of supplying aquaria and their contents.

Many houses were already furnished with glazed terrariums – conversation pieces housing delicate plants – so aquariums were the next fashionable step. The Glass Duties Repeal Act (1845) made industrial plate glass cheaper and so retailers like Lloyds in London sold prefabricated ‘parlour pond’ tanks at prices that further fueled the mania (Newman, 1873).

The novelty of a glass-fronted natural theatre quickly waned as domestic aquarium husbandry proved taxing for many. One Victorian aquarist wrote that whilst ‘Aquarium mania’ had now passed, for the serious student, aquariums remained “a triumph of art acting as the handmaid of science.” (Hibberd, 1860 pp.2-3).

How did the public aquarium develop in Britain?

Anna Thynne (1806-1866) is credited with opening London’s first biologically balanced marine aquarium when she put her corals and sponges on public display at Westminster Abbey in 1847 (Stott, 2003). In the wake of the extravagant displays of the London’s Great Exhibition (1851) and its glazed Crystal Palace complex, aquariums increasingly looked to exploit the “mass transparency” of glass to satisfy a spectacle-hungry population (Armstrong, 2008).

In 1853, a ‘Marine Vivarium’ opened in Regent’s Park Zoological Gardens, London. Dubbed ‘The London Fish House’, it kept its crabs, molluscs, and fish healthy with little need for aeration or water changes. Its success led to other aquariums opening in Britain, Europe, and the U.S.A in the next two decades.

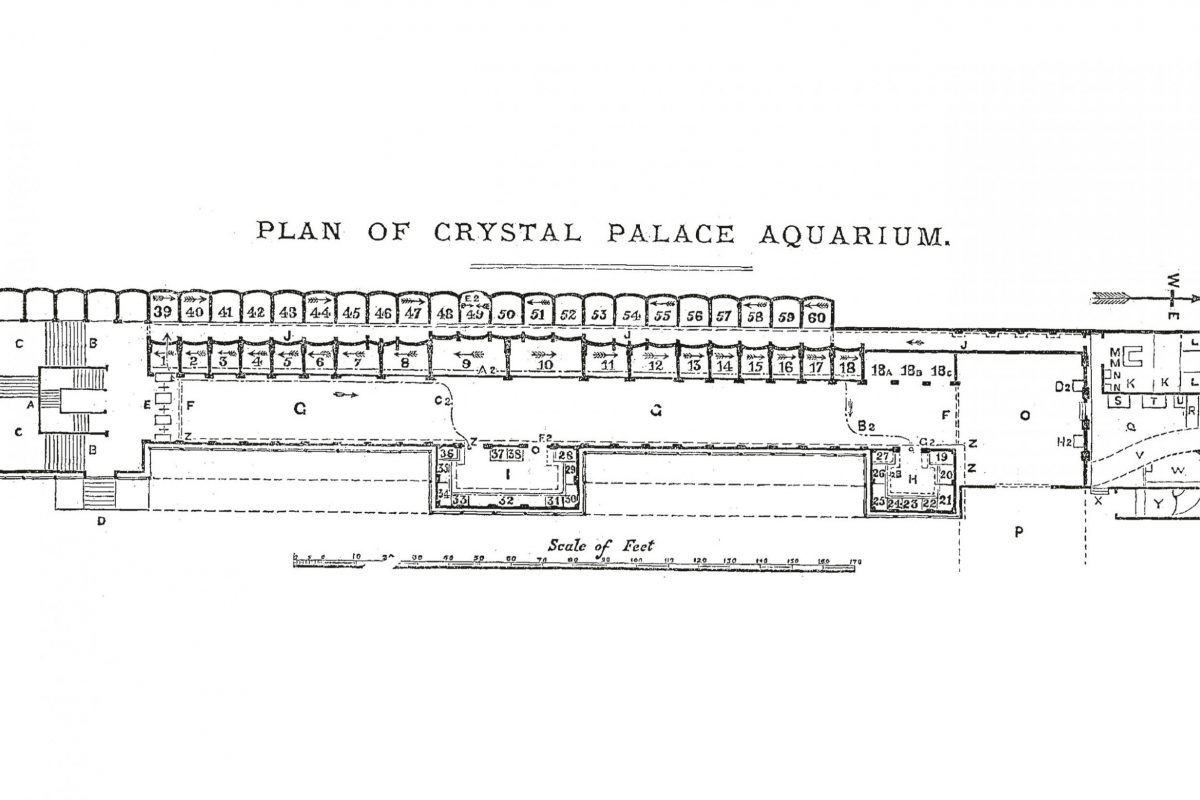

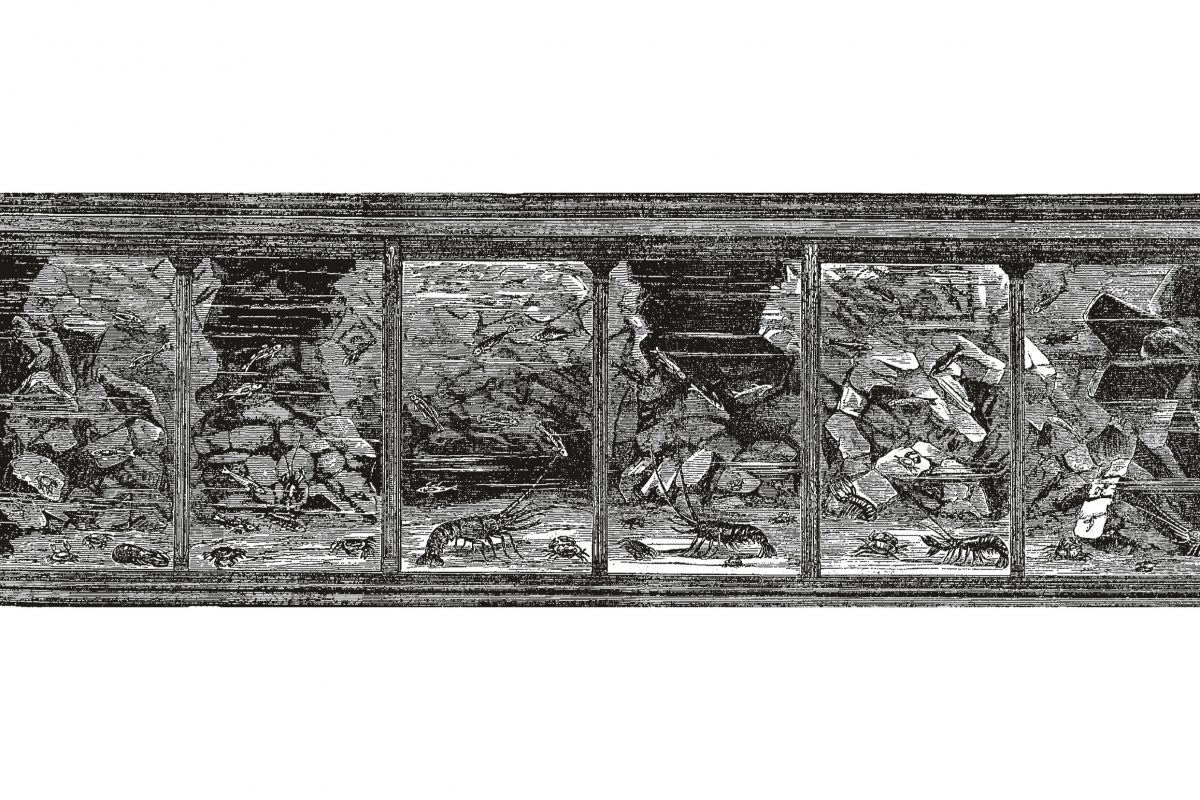

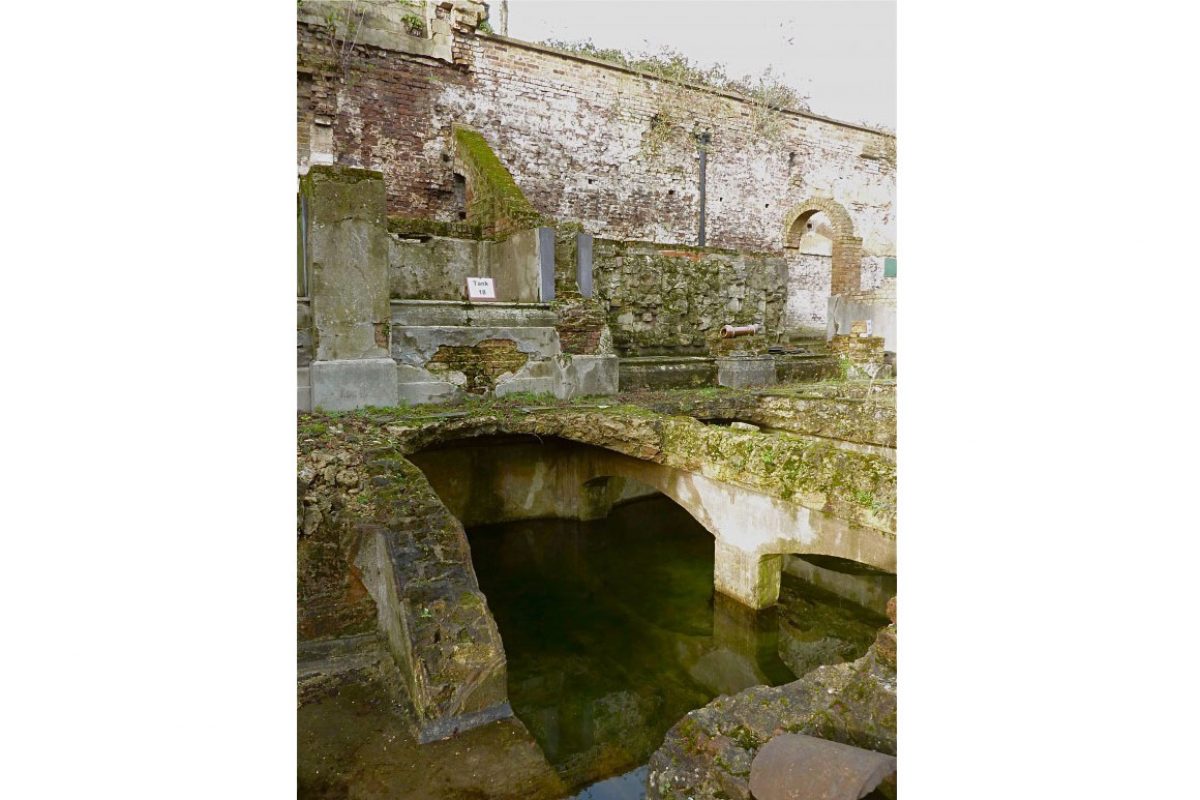

In 1871, Britain’s first large-scale aquarium opened in a basement of the re-sited Crystal Palace structure in South London. It relied on casks of seawater brought by train and a steam-driven circulation system devised by its Superintendent, the retail aquarist William Alford Lloyd (1826-1880).

In this extensive public aquarium, under-floor reservoirs and non-corrosive vulcanite pipes fed sixty-one tanks at a rate of 5-7,000 gallons an hour. 22 of these were reserved for behind-the-scenes research (Lloyd, 1871).

Its remains are still visible.

How has the Horniman Aquarium evolved?

There is an advantage in finding together within the space of a few square yards, animals typical of a variety of habitats.

In 1901, Frederick John Horniman (1835-1906) presented his private collection of artefacts and natural specimens to the people of London.

The collection was housed in a new museum building in Forest Hill and included a corridor serving as a ‘living extension’ to the Natural History galleries (Robson, 2013 52). The curators first used table displays of jars and dishes, before adding 47 slope-fronted tanks in 1907.

Perhaps the small aquarium corridor was seen as a modest replacement for the popular but now bankrupt Crystal Palace Aquarium less than two miles away. However, the appointment of zoologist and anthropologist Alfred Cort Haddon as Advisory Curator in 1902 marked a strong shift of focus away from entertainment in Forest Hill towards the educational (Shelton, 2001).

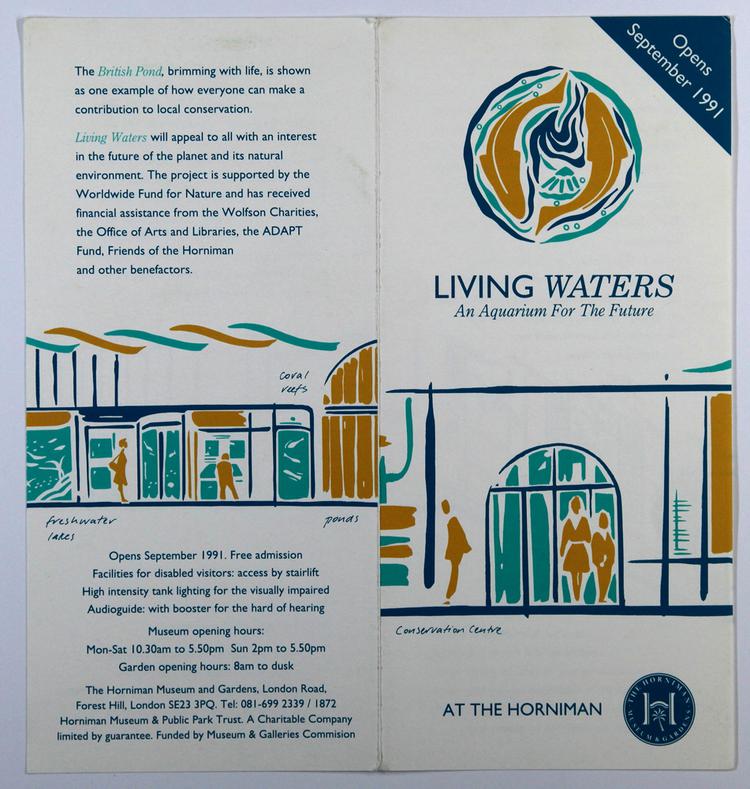

Following a period of stagnation and some public criticism, conservation-led redevelopment and reorientation of the aquarium took place in 1991 and again in 2006 with habitat simulation playing a key feature.

Leaflet: Horniman Museum: Living Waters: An Aquarium from the Future, 1991

Archive

The aquarium reinvented

Despite best efforts, many public aquariums suffered decades of technical shortcomings that impacted on animal welfare levels. High animal mortality rates were routinely countered with seasonal restocking (Reid, 2001).

Matters improved at the end of the twentieth century when well-run research aquariums and institutes with stable tank ecologies and healthy stock became models for mainstream reinventions. Public aquariums with improved husbandry regimes could now respond to critical public voices and prioritise an emerging conservation agenda.

New generation aquariums like the Monterey Bay Aquarium (1984) used acrylic not glass for their vast tanks because of superior light transmission, insulation and flexibility. Today, all large-scale aquariums feature acrylic tunnels to surround their visitors with water and fishes, achieving what has been called ‘immersion exhibitry’ (Reid, 2001).

Tanks are also used backstage for “mimetic experimentation” (Golinsky, 2005 p.98). This is where aquarium-centred conservation and restoration projects faithfully imitate natural ecosystems.

One example is that of the Horniman Aquarium’s behind-the-scenes work on captive coral breeding. This involves simulating ecosystem data gathered from wild reefs in Fiji and Guam.

Temperature and moonshine are tracked, transmitted then replicated in the aquarium’s research tanks in Forest Hill, South London.

In this way, Horniman aquarists are now observing the complexity and fragility of a wild reality, in controlled backstage conditions.

Posting this aquarium research and breeding success online means that for the first time, the public are able to observe off-display lab tanks in a virtual way.

Sources

- Armstrong, I., 2008. Victorian Glassworlds: Glass, culture and the imagination, 1830-1880. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brock, W.H., 1991, ‘The Warrington-Gosse Aquarium Controversy: Two un-recorded letters’, Archives of Natural History 18 (2): 179-183.

- Brunner, B., 2011, The Ocean at Home: An Illustrated History of the Aquarium. London: Reaktion Books.

- Golinsky, J., 2005. Making Natural Knowledge: Constructivism and the history of science Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Hibberd, S., 1860. The Book of The Aquarium; or Practical instructions on the formation, stocking and management in all seasons, of collections of marine and river animals and plants. A new edition revised and enlarged. London: Groombridge and Sons.

- Lloyd, W.A., 1871. ‘Crystal Palace Aquarium’, Nature 4, October 12, 1871 469-473.

- Newman, E., 1873. A series of articles by Edward Newman. Zoologist, 1873, Second Series – Vol. VIII.

- Pepys, S., 1665. Sunday 28 May 1665.

- Reid, G. McGregor, 2001. ‘Conservation in the Growth and Development of Public Aquaria’, Bulletin de l’Institut océanographique, Monaco, no. special 20, fascicule 2.

- Robson, J., 2013. ‘History and Future of Horniman Museum Aquarium, London’, a pdf kindly supplied by James Robson.

- Shelton, A., 2001. ‘Rational Passions: Frederick John Horniman and Institutional Collectors’ Collectors: Expressions of Self and Other, 205-223 Anthony Shelton (ed.). London: The Horniman Museums and Gardens & Coimbra: Museu Antroplógico da Universidade de Coimbra.

- Stott, R., 2003. Theatres of Glass: The woman who brought the sea to the city. London: Short Books Ltd.

- Wood, J.G., 1868. The Fresh and Salt-Water Aquarium. London: George Routledge & Sons.