Endurance

On 8 August 1914, as the First World War was beginning, the steam yacht Endurance left Plymouth. Along with its owner Sir Ernest Shackleton, it was headed for Antarctica.

Both Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott had already reached the South Pole in 1912. Shackleton intended to cross the continent of Antarctica via the Pole.

Despite this plan being in place, Shackleton offered the ship and its crew to the Admiralty, in the face of war in France. In response to this Shackleton received a reply directly from the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill: ‘Proceed.’

Three years later, Shackleton and his men arrived in Punta Arenas in Chile. They had failed even to set foot on the Antarctic mainland.

Endurance had been frozen into the pack ice in the Weddell Sea and drifted for 1300 miles and 282 days before being crushed. The crew had moved onto the pack ice, where they camped and drifted for another 165 days before taking to the Endurance’s three open boats and rowing for six days to reach the desolate and uninhabited Elephant Island.

The majority of the crew stayed there, living on what they could hunt, in a low hut roofed with two of the boats. Shackleton and five companions sailed the third boat, the James Caird, across 800 miles of the world’s stormiest seas to reach South Georgia.

Once they had arrived, Shackleton, Frank Worsley and Tom Crean walked almost non-stop for 36 hours without equipment across the ice-capped, mountainous island to reach the whaling station at Stromness, and to get help.

Antarctica and the Horniman

What does this tale have to do with the Horniman? After all, Antarctica is unique as a continent in having no native culture, whose material culture we might collect.

But the Horniman did once have a collection of objects related to Antarctica. These came to light as a result of the Collections People Stories and Bioblitz projects.

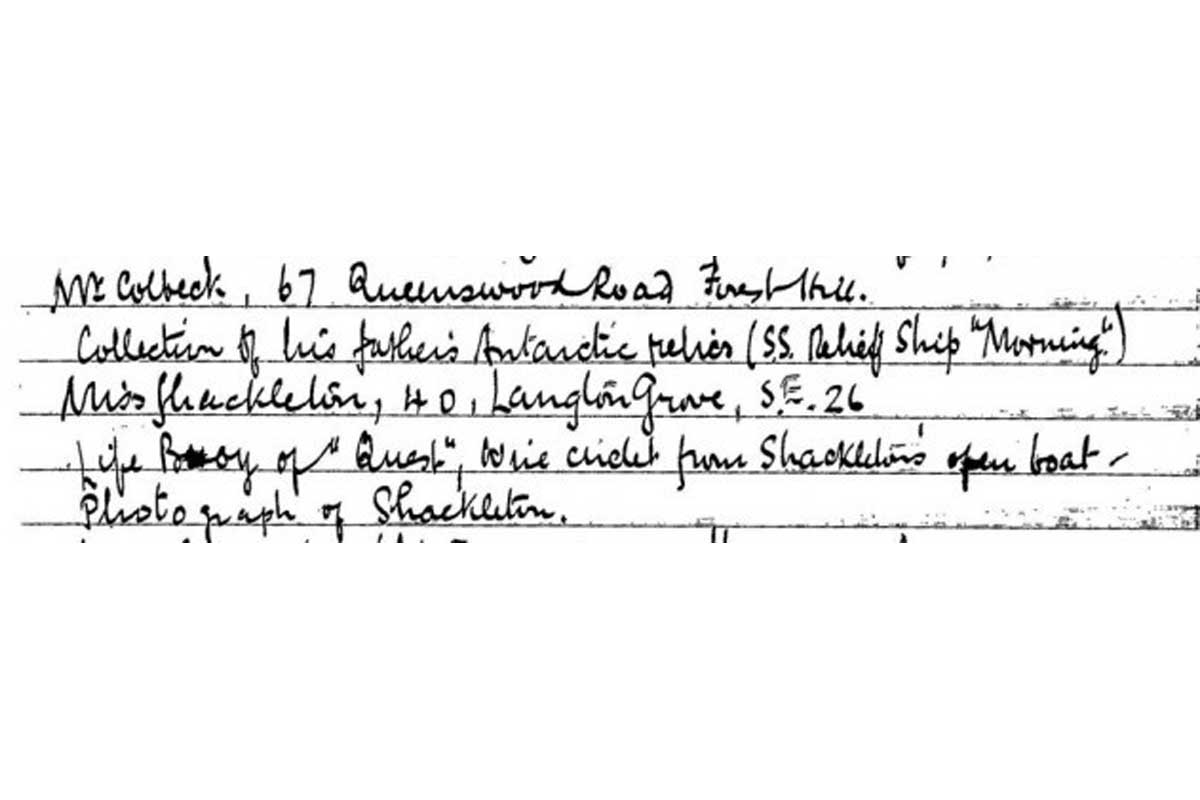

I first came across a record of Antarctic objects in the Horniman when my colleague Rachael Utting, working as a Documentation/Collections Assistant on the Collections People Stories project, came to me with a page from the Museum’s accessions register for 1938.

What is an accessions register?

The accession registers are a museum’s formal record of the objects which make up its collections.

They should provide a clear description of each object, give it a unique identifying number (the object’s ‘accession number’), and state how and when it was acquired, and from whom.

Although usually quite well-maintained, the Horniman’s anthropology registers over the period from 1938 to 1959 (coinciding with the curatorships of L. W. G. Malcolm and Otto Samson) leave much to be desired. However, this entry said enough to spark my curiosity.

It listed a donation from a Miss Shackleton of a ‘Life Buoy of “Quest”, Wire circlet from Shackleton’s open boat – Photograph of Shackleton.’

The Wire Circlet and Quest

The ‘wire circlet’ could only be a relic of that 800-mile open boat journey from Elephant Island to South Georgia, a piece of the James Caird herself.

Although Shackleton was a sailor, he did serve as a major in the British army from July 1918 to March 1919, primarily in northern Russia; the photograph must date from this period.

The lifebuoy would have come from the RYS Quest, a small ketch-rigged seal-hunting ship with an auxiliary steam engine bought by Shackleton for his final Antarctic expedition. It was during this expedition that he died, onboard Quest on 5 January 1922. Quest was later used for the British Arctic Air Route Expedition.

Who was Miss Shackleton?

Miss Shackleton would have been one of Sir Ernest’s sisters, either Gladys Mabelle Shackleton (1887-1962) or Amy Shackleton (1875-1953), both of whom were living at the address listed in the register at the time. It is possibly Alice Shackleton (1872-1938), who may have been living with Gladys and Amy when she died.

Whoever she was, the Horniman was a logical place for Miss Shackleton to place these objects.

Although Anglo-Irish by descent, the Shackletons were a local family, living in Sydenham, which had long been the site of the family home.

Their father had moved to Aberdeen House in West Hill, Sydenham, in 1884 or 1885, where he practiced as a doctor. The young Ernest went to the nearby Fir Lodge Preparatory School in 1885, before being sent to Dulwich College from 1887 until 1890, when he went away to sea.

Finding the objects

Because they had been accessioned – or made part of the Horniman’s collections – these three objects had been recorded on our collections database. However, they had not been given a location. Although Rachael and I both looked immediately for the lifebuoy – which we knew from photographs taken on the Quest must be fairly large – we couldn’t find it.

William Colbeck

Just above the Shackleton entry, there was another equally interesting entry.

A Mr. Colbeck, living in Forest Hill, had given us a ‘Collection of his father’s Antarctic relics (S.S. Relief Ship “Morning”.)’

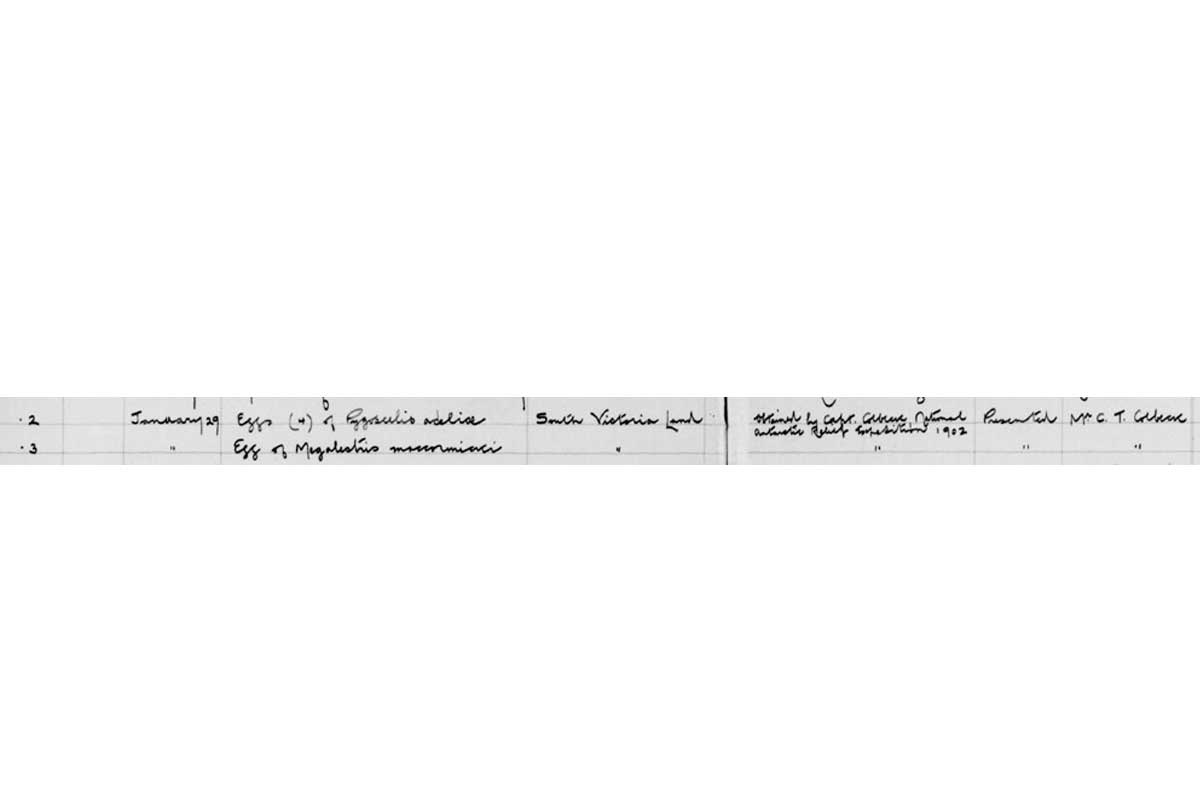

A quick check of the separate registers maintained by the natural history collection provided a little more detail about some of the objects. Received on 29 January 1938 were listed:

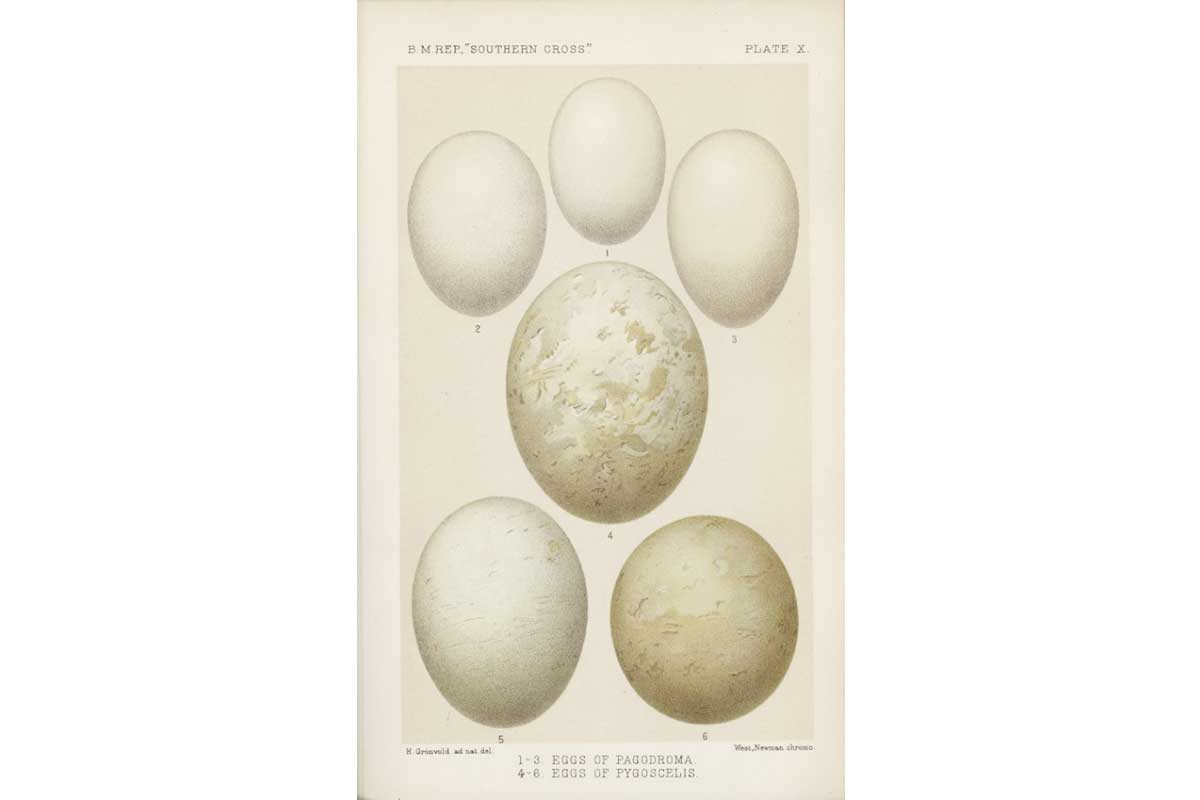

- ‘Eggs (4) of Pygoscelis adeliæ’ – of the Adelie penguin

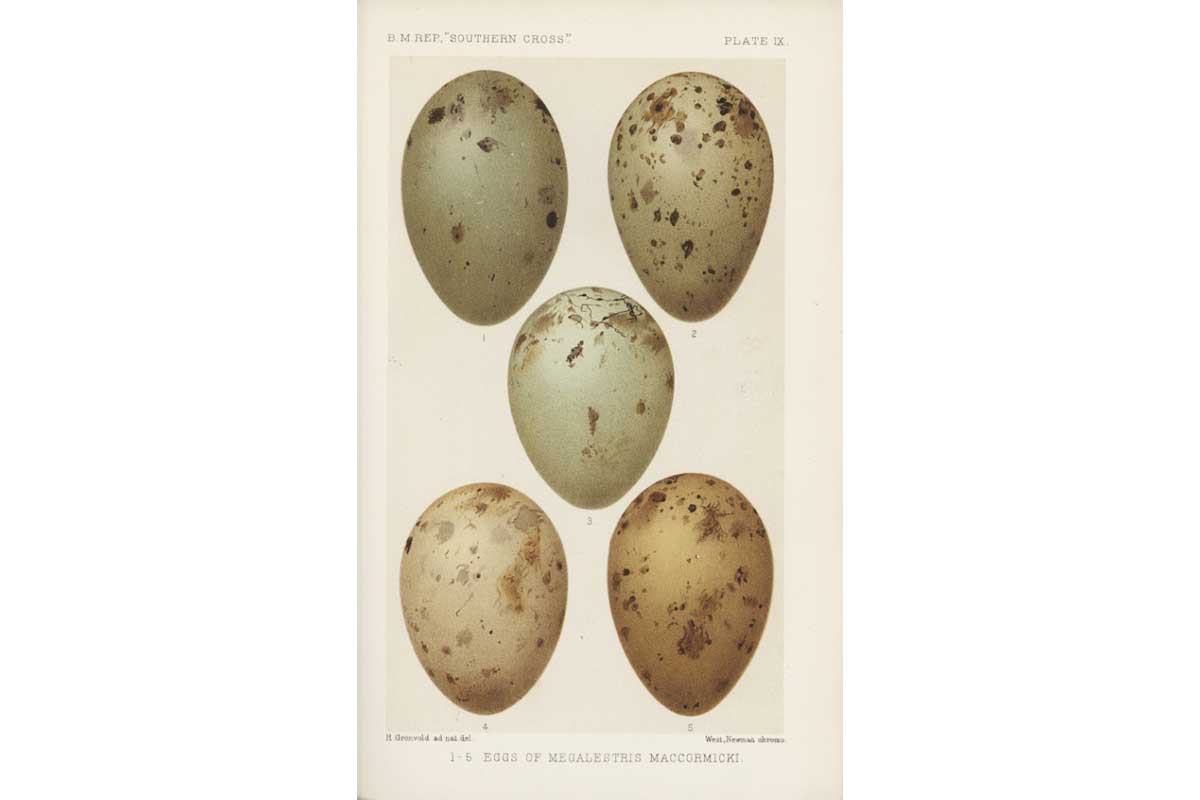

- ‘Egg of Megalestris maccormicki’ – of the Antarctic Skua, now named Stercorarius maccormicki

Both were collected in South Victoria Land where they were ‘Obtained by Capt. Colbeck, National Antarctic Relief Expedition 1902’.

Who was William Colbeck?

Although little-known today, Colbeck was once one of the most experienced Antarctic sailors.

Apprenticed into the Merchant Marine aged 15, in 1898 he joined Carsten Borchgrevink’s British Antarctic Expedition (the Southern Cross expedition). This was the first to spend the winter ashore in Antarctica. Colbeck was one of those responsible for making measurements of the Earth’s magnetic field, and his readings helped identify the position of the South Magnetic Pole.

Two years after his return from Antarctica in 1900, Colbeck – aged only 31 – was given the command of the Morning. He was sent to relieve Captain Scott’s British National Antarctic Expedition whose ship, the Discovery, had been frozen into the ice at the far end of McMurdo Sound.

Colbeck found the Discovery, but it remained frozen in, 10 miles from the open sea.

He was only able to resupply Scott’s expedition before returning to New Zealand, carrying a disgruntled Shackleton, who had been invalided home after becoming seriously unwell during his trek to reach a new farthest south of 82º 17″ with Scott and E. A. Wilson.

This was the ‘National Antarctic Relief Expedition 1902’ referred to in our natural history register.

The Antarctic Skua eggs

If the eggs really were collected in ‘South Victoria Land’ during that expedition, then they must have come from Cape Adare, where Colbeck had previously spent the winter with Borchgrevink. He does not seem to have landed anywhere else in Victoria Land during the relief expedition.

The following year, Colbeck was sent back to McMurdo Sound in overall command of the Morning and the more powerful Terra Nova.

He had orders to retrieve Scott’s expedition regardless, abandoning the Discovery if necessary. But the ice cleared out of McMurdo Sound at the last possible moment, and all three ships returned to New Zealand in April 1904.

Three years later, Shackleton asked Colbeck to captain the Nimrod for his British Antarctic Expedition. Despite being offered a £500 salary and £2,000 bonus if the expedition were a success, Colbeck declined. He recommended instead that Shackleton take his old first mate from the Morning, Rupert England.

One of Colbeck’s four sons, W. R. Colbeck, continued his father’s Antarctic connections, sailing with Sir Douglas Mawson on the Discovery in the British Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (or BANZARE) voyages from 1929 to 1931. But the natural history register states that the eggs were presented by another son, C. T. Colbeck.

The paper trail

So far I’ve mentioned eight interesting objects about which I wanted to know more:

- The wire from the James Caird

- Photograph of Shackleton

- Questlifebuoy

- Skua egg

- Four penguin eggs

However I had only been able to produce cursory written records for them dating from 1938, copied into our database, with no idea of where the objects are now or what had happened to them.

Another part of our documentation has also helped me unravel something of the fate of these, and other, Antarctic objects.

Lady Kennet

The Anthropology Department’s history files – where we keep miscellaneous information about the objects in our collections – are organised by the name of the person from whom we acquired the objects. Searches for Colbeck and Shackleton had proved fruitless. However Chris Olver, our archivist, found a file under the name Scott/Kennett.

This is a reference to Captain Scott’s Wife Kathleen Scott, née Bruce. She later became Lady Scott and after her second husband was ennobled, Lady Kennet.

Under Scott/Kennet we found information about the Colbeck and Shackleton objects.

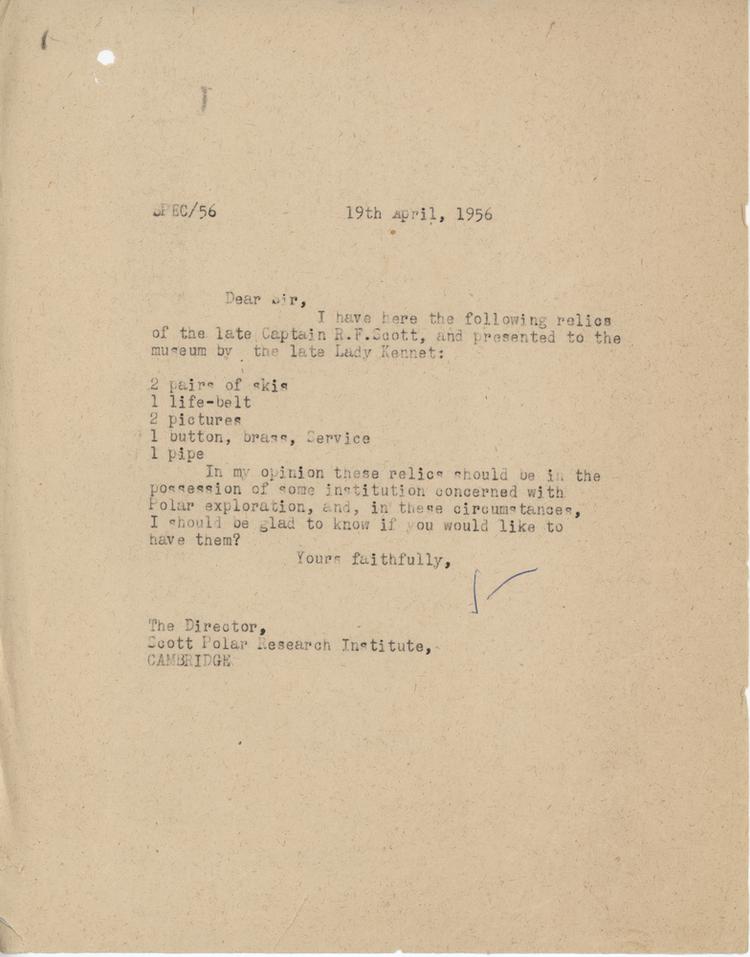

Letter by Otto Samson to the Director of the Scott Polar Research Institute, regarding the transfer of Captain Scott relics

Archive

In 1938, someone – we assume the Horniman’s Curator (i.e. director), L. W. G. Malcolm – seems to have written to Lady Kennet, asking for some mementoes of her late husband.

We have Lady Kennet’s reply of 8 March, suggesting that she might send an old pipe, tent poles, pair of skis, or naval button from Scott’s coat.

Following the Museum’s reply the following day, Lady Kennet sent the pipe and button on 14 March; the skis were to follow later, by messenger. This is the first reference we have to these items, which never found their way into the accession registers.

Moving the objects

The trail then turns cold until 24 February 1956. The Horniman’s Curator, the anthropologist Otto Samson, wrote to John Brown, the Education Officer at the London County Council (who at that time ran the Horniman), asking that the Advisory Committee responsible for the Museum give him permission to dispose of:

‘some relics of Captain Scott, R.N.’, comprising ‘skis, lifebelt, pictures, button (uniform service brass) and pipe’.

These used to be on show in the South Hall, but by 1956 had been removed from display. Samson felt that ‘these relics of a national hero would be more suitably housed at the Polar Research Institute at Cambridge [the Scott Polar Research Institute] or the Royal Geographical Society than in a museum devoted to Ethnography and Natural History’.

Letter by Otto Samson regarding potential disposal of Captain Scott relics from the Horniman Museum

Archive

Interestingly, Samson also mentions that the objects were ‘collected … from Commander Bernacchi’, not Lady Kennet, or Miss Shackleton – from whom we acquired the Quest lifebuoy and picture of Shackleton.

He also mentions ‘pictures’ (plural), although the registers only mention the Shackleton photograph. These might come under the heading of Colbeck’s ‘Antarctic relics’ as described in the register, though what the correspondence later reveals about the date of the extra picture makes this unlikely.

This is also the first mention of Commander Bernacchi, who might conceivably have been Lady Kennet’s messenger: Louis Bernacchi was another notable Antarctic explorer, serving as the other magnetic observer alongside Colbeck in Borchgrevink’s Southern Cross expedition, and the physicist on Scott’s Discovery expedition.

The correspondence continues: Brown asked Samson to confirm that the Scott Polar Research Institute and Royal Geographical Society were willing to accept the objects; Samson confirmed that the Director of the Royal Geographical Society thought they should first be offered to the Scott Polar Research Institute; Samson was asked to inform Scott’s son, Sir Peter Scott, of the intended disposal, and did so; Sir Peter replied with his agreement.

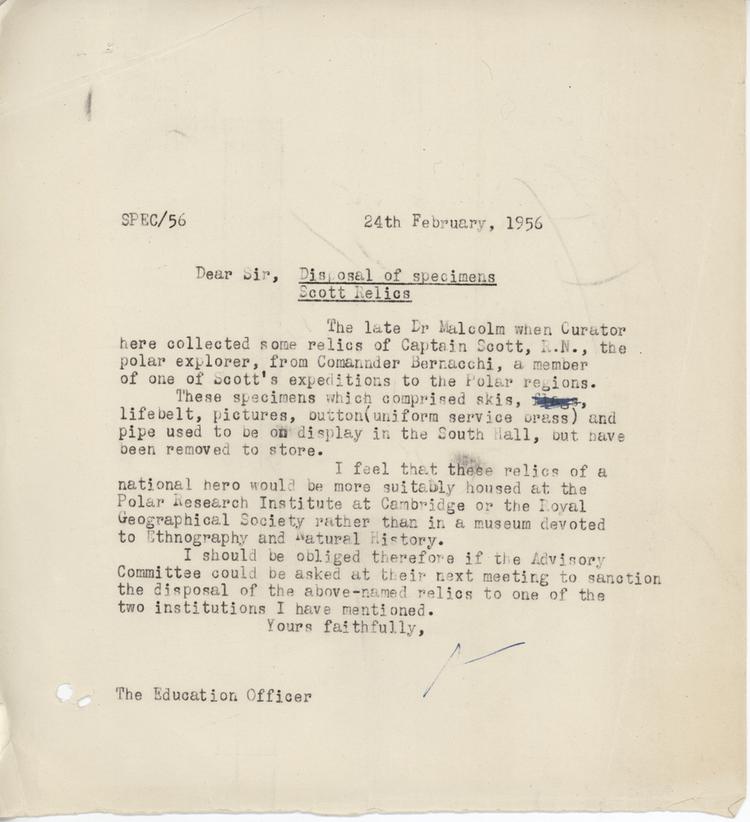

On 19 April, Samson wrote to the Scott Polar Research Institute, offering them a series of items ‘presented to the museum by the late Lady Kennet’:

- 2 pairs of skis

- 1 life-belt

- 2 pictures

- 1 button, brass, Service

- 1 pipe

The reference to Bernacchi has disappeared, but we still have the extra picture and now an additional pair of skis.

L. M. Forbes, the curator of the Scott Polar Research Institute’s museum and photograph collections, asked for more information about the lifebuoy and pictures; Samson told him that the lifebuoy came from the Quest, and that the pictures comprised the photograph of Shackleton – and a ‘Water colour entitled “Sledge Hauling” and signed “Wilson”, and dated Mar 1911’.

Letter by Otto Samson to the Director of the Scott Polar Research Institute, regarding the transfer of Captain Scott relics

Archive

Edward Adrian Wilson

This would have been a reference to one of the many watercolours produced on the Terra Nova expedition by Edward Adrian Wilson, who had died alongside Scott and Henry Bowers on their return from the South Pole.

Wilson was a doctor and zoologist, who had travelled with Scott on the Discovery expedition as assistant surgeon and vertebrate zoologist, setting the furthest south record alongside Scott and Shackleton. On the Terra Nova expedition, he was chief of the scientific staff. Wilson was also a highly-talented artist, producing many hundreds of extremely accurate drawings and watercolours of the geography and fauna of Antarctica during the two expeditions.

Sledge Hauling is unlikely to have painted whilst sledging on the ice – the water needed to mix the paints would have frozen. It must have been done some time after 5 March, when Wilson, Scott, and several others, after laying depots on the Ross Ice Shelf for the coming attempt on the South Pole, were camping out in the old Discovery hut at Hut Point on Ross Island.

Where are they now?

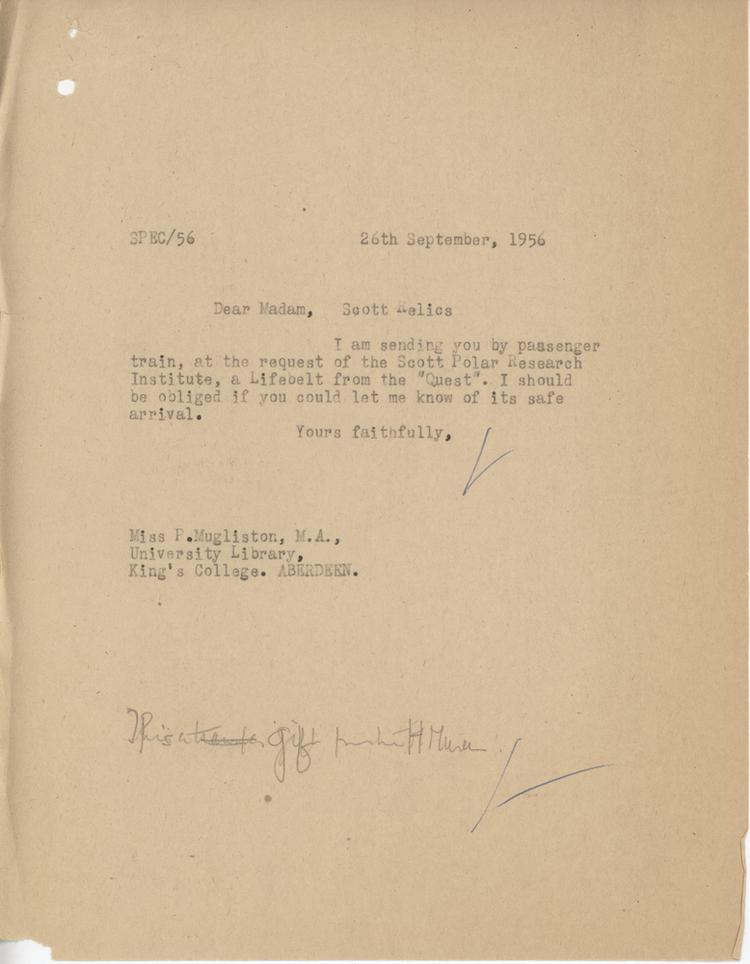

Quest lifebuoy

The Quest lifebuoy was sent ‘by passenger train’ to a Miss P. Mugliston in Aberdeen, who seems to have acted on behalf of the Sea Rangers there; she acknowledged its receipt on 4 October.

Here, the trail runs cold. I have been told that the crew of the SRS Quest was presented with a lifebelt from the original Quest by Captain Scott’s widow, and that it is now in the Aberdeen Maritime Museum. But, as we have seen, the lifebuoy came from the Horniman (and Lady Kennet had died in 1947); and the Aberdeen Maritime Museum have kindly searched their records for me and found no trace of the Quest’s lifebuoy. I’ve made enquiries of other Scottish maritime museums, to no avail.

Letter by Otto Samson to P. Mugliston, regarding the despatch of Captain Scott relics

Archive

Pictures

As the two pictures were glazed, Samson did not wish to trust them to the post. They were eventually collected on 11 December 1958 by the Scott Polar Research Institute’s Assistant Librarian and Keeper of Prints and Drawings (and a notable Polar historian), Ann Savours. The Wilson ‘drawing’ is no Y: 56/29 in the Scott Polar Research Institute’s catalogue of works of art. In fact, it is a facsimile of a watercolour, rather than an original, one of a set published by Wilson’s widow, Oriana, in the 1930s to raise money for charity. The location of the watercolour which it reproduces is currently unknown, but another copy of the print has been reproduced online.

Letter by Otto Samson to Ann Savours, regarding the collection of Captain Scott relics from the Horniman Museum

Archive

Unfortunately, the Scott Polar Research Institute’s records show that, shortly after the Shackleton photograph arrived, it was found to be mildewed and was disposed of. It was presumably like the photograph apparently taken in 1918 by F. A. Swaine, and included in H. R. Mill’s 1923 biography of Shackleton.

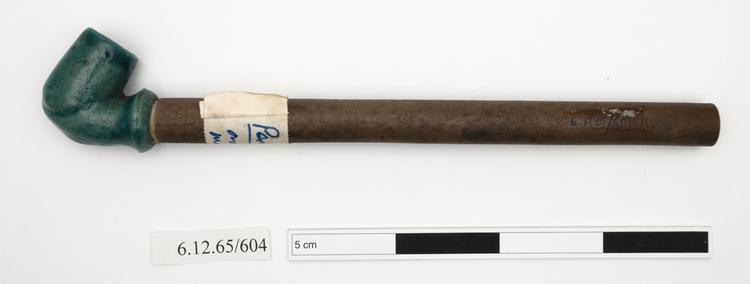

Button and pipe

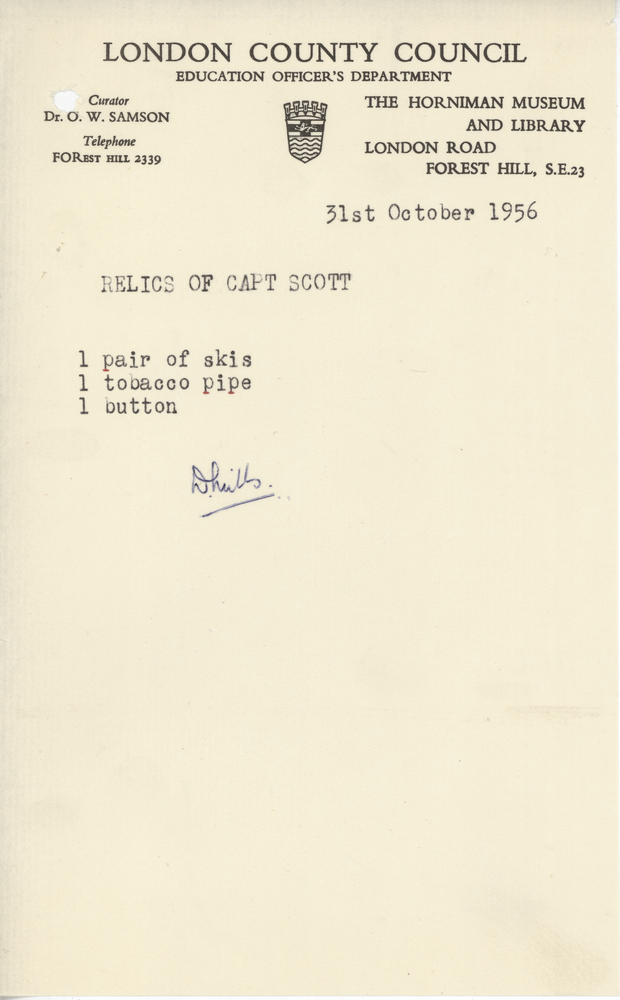

The button, pipe, and one pair of skis were collected from the Horniman by a representative of HMS Discovery on 31 October 1956. After that, their provenance can be traced along with the ship.

Receipt for three Captain Scott relics dispatched to HMS 'Discovery'

Archive

In 1979, HMS Discovery (henceforward RRS Discovery) was transferred to the Maritime Trust. In 1985, she was chartered to Dundee Heritage Trust and the Scottish Development Agency, arriving in Dundee on the back of another ship in April 1985. There, she became the focal-point of Discovery Point, a visitor centre and museum centred around the ship which opened in 1993.

In 1995, the Discovery, and the Maritime Trust’s collections which had been in store at the National Maritime Museum, were purchased by Dundee Heritage Trust for a nominal sum. In an article in the Museums Journal, Gill Poulter of Dundee Heritage Trust remembers hiring a van, driving down to London with a colleague, and bringing the collections to Aberdeen to rejoin the ship.

It seems from the Dundee Heritage Trust’s records that the pipe and button arrived slightly earlier than the actual purchase from the Maritime Trust, in December 1994.

The missing skis

The skis are more of a problem. Dundee Heritage Trust acquired two pairs from the Maritime Trust. W 79.133.69 is clearly labelled as having belonged to Reginald Skelton, Lieutenant (R.N.) and engineering officer on the Discovery expedition. I can think of no reason why Lady Kennet should have owned them, or sent them to the Horniman as Scott’s.

The fact that the Trust have several other objects which belonged to Skelton makes me think that at some point, the Maritime Trust had acquired a collection of items from Skelton or his descendants.

W 79.133.68 might be Scott’s skis – but they are marked ‘W.C.’ No-one with those initials served on Scott’s Discovery or Terra Nova expeditions – though they might, intriguingly, have been William Colbeck’s. But again, why would Lady Kennet have had them?

This brings us back to Bernacchi, mentioned by Samson in connection with the Antarctic objects, who was a friend of Colbeck’s during the difficult Southern Cross expedition, and would go on to write a short obituary of his former companion for the Times. Might he have given these skis to the Horniman, along with the Wilson watercolour, at the same time as acting as Lady Kennet’s intermediary regarding Captain Scott’s skis?

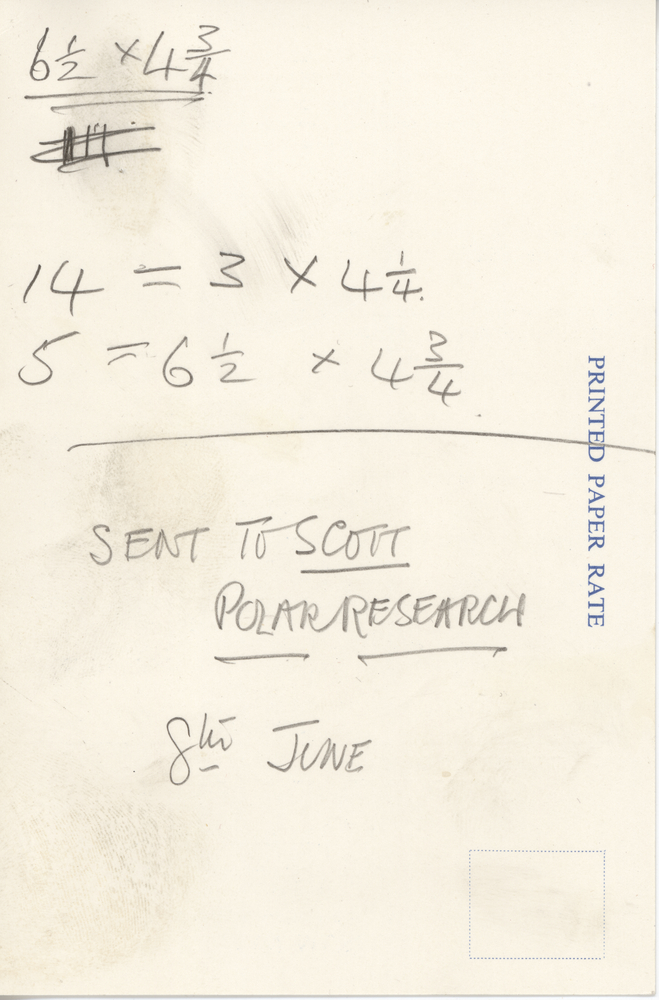

Of Colbeck’s objects, we have so far identified the four penguin eggs and one skua egg, and possibly a pair of skis; but there were more. A later letter from Samson in the Kennet history file [038] offers ‘a number of plates by Capt. Colebeck [sic] “National Antarctic Expedition, 1900-1904″‘ to the SPRI on 2 June 1961; these were accepted by Forbes on the following day [039], and, according to a brief note [040], despatched on 8 June. The note also allows us to identify precisely what was meant by plates, as it lists their quantities and dimensions:

14 = 3 x 4¼

5 = 6½ x 4¾

Both of these are standard sizes for photographic plates, or glass negatives (possibly, in this case, positives): 3¼ x 4¼” is the size known as ‘quarter-plate’; 6½ x 4¼” is ‘half-plate’ (a whole plate was, obviously enough, 6½ x 8½” in size). The National Antarctic Expedition 1900-1904 is of course Scott’s first expedition. So at one time we had 14 quarter-plate photographs and 5 half-plate photographs, apparently taken by William Colbeck, of the Discovery expedition. These are presumably the ten prints and six negatives listed by the SPRI under numbers P62/44/1-10 and P62/45/1-6 respectively, as presented by Captain Colbeck. SPRI staff are currently checking where these are stored.

Adélie Penguin eggs

These eggs were found as the team were working through the collection of birds’ eggs whilst following up the results of the Museum’s Bioblitz collection review.

They are clearly identified by accompanying paperwork, and in fact, comprise four Adélie Penguin eggs and two (not one) Antarctic Skua eggs.

They were presented by Clements Markham (‘Mark’) Colbeck (not C. T. Colbeck), one of William Colbeck’s sons, but, as he was living in Deptford at the time, probably not the son who donated the ‘relics’ recorded in the anthropology register, who was then living in Forest Hill.

According to information provided by Mark Colbeck’s daughter, Sandra Margolies, the latter was most likely John Christopher Colbeck, known as Chris, Mark’s brother and Captain Colbeck’s son.

Documents and Heroes

So, the Horniman’s documentation – imperfect as it is – has allowed us to identify a series of ‘Antarctic relics’ which were once in the collections and are now elsewhere:

At Discovery Point:

- Captain Scott’s pipe, given by his widow, Lady Kennet

- A button from Captain Scott’s uniform coat, also given by Lady Kennet

- Possibly a pair of Captain Scott’s skis, also given by Lady Kennet

- Possibly a second set of skis, which may have been given by Louis Bernacchi

At the Scott Polar Research Institute:

- Facsimile of E. A. Wilson, Sledge hauling, watercolour, March 1911, possibly given by Louis Bernacchi

- 14 quarter-plate photographs and 5 half-plate photographs, apparently taken by William Colbeck, of the Discovery expedition, given by his son C. T. Colbeck

Formerly at the Scott Polar Research Institute:

- A photograph of Sir Ernest Shackleton in military uniform, given by one of his sisters, Miss Shackleton

Formerly with the SRS Quest:

- A lifebuoy from the RYS Quest, given by Miss Shackleton

Eggs presented by Clements Markham Colbeck

- Four Adélie Penguin eggs,

- Two Antarctic Skua eggs, given by William Colbeck

We now have a reduced set of objects which may still be in the Horniman’s stores at the Study Collections Centre, and for which we are keeping an eye out:

- Possibly the second set of skis, which may have been given by Louis Bernacchi

- A wire circlet from the James Caird, given by Miss Shackleton

The context of acquiring the objects

And now that we’ve identified these objects, we can understand a little more about the context within which they were acquired.

I’ve consciously referred to them throughout this piece using Malcolm’s and Samson’s phrase, ‘Antarctic relics’ because that gives an idea of how I believe they were regarded at the time of their acquisition.

The expeditions from which they originated – Scott’s Discovery and Terra Nova expeditions, and Shackleton’s Endurance expedition, along with the Discovery relief expeditions – all fall into the period of Antarctic exploration known as the ‘Heroic Age’.

This was the era – roughly from 1897 to 1922 – when knowledge of the continent was hugely expanded by a series of expeditions, whose participants were gradually learning how to live and work in one of the least hospitable places on earth.

Along the way, many of the expeditions’ members suffered great discomfort and hardship, and several died; they also carried out phenomenal feats of strength and endurance.

Whatever one may think of the preparations they made and the techniques they used, no one can doubt their courage.

Because of its tragic ending, the quintessential expedition of the Heroic Age is perhaps Scott’s last expedition.

When news of the deaths of Scott and his companions reached Britain on 10 February 1913, it provoked an unprecedented outpouring of public grief.

As the details emerged of PO Evans’s collapse, Captain Oates’s self-sacrifice (‘I am just going outside, and maybe some time’), and Bowers’, Wilson’s, and Scott’s deaths trapped by a blizzard only eleven miles from One Ton Depot, this was augmented by respect for the way the explorers had met their deaths, helped in large part by the dying Scott’s eloquent Message to the Public:

Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale…

The horrific events of the First World War, where so many millions found their hardihood, endurance and courage tested, and hundreds of thousands made the ultimate sacrifice, only increased the admiration felt for the noble way in which Scott and his companions had met their ends.

Indeed, Herbert Ponting’s film of the expedition is known to have been shown to over 100,000 officers and men on the Western Front, providing them with an example of how Englishmen could face adversity.

It is significant, I think, that Dr Malcolm approached Lady Kennet for some mementoes of her husband early in 1938, the year after the twenty-fifth anniversary of her husband’s death had seen a renewed interest in the expedition, by now firmly established as an exemplary tale of British manhood.

Although her donation to the Horniman does not appear in the registers, I think it is also significant the objects relating to Colbeck and Shackleton should appear in the same year as Lady Kennet’s gifts, and immediately next to each other.

I suspect that Malcolm, prompted by the anniversary of Scott’s death, was trying to create a small shrine of relics of Antarctic heroes in south-east London, combining national heroes (Scott) with those who had local connections (Shackleton and Colbeck). We know from Samson’s first letter that these had been displayed together in the Horniman’s South Hall (now the World Gallery).

We also know that, less than twenty years later, they were no longer on display.

Otto Samson, who – as a German émigré who had fled the Nazi persecutions and lived through the Second World War – did not, perhaps, feel quite the same unquestioning admiration for heroic self-sacrifice as his predecessor, considered that these relics had no place in a ‘museum devoted to Ethnography and Natural History’.

But history may, in the end, be proving him wrong: with the birth of Emilio Palma in 1978, it could be argued that Antarctica has the beginnings of a native population; it certainly has a series of permanent rotating populations, with a series of what often seem to be quite particular cultures – for example, the Big Eye parties, or the exorcism of El Gran Chingazo.

By deaccessioning our Antarctic relics, Samson inadvertently deprived us of early specimens of the ever-increasing material culture of Antarctica.

The Heroic Age and colonialism

This ‘Heroic Age of Arctic Exploration’ was different from other colonial expansion, in that there were no human cultures in Antarctica. Antarctica was therefore deemed a terra nullius, meaning unoccupied or uninhabited land, which meant that under international law states could claim Antarctic territory for themselves by exploring and occupying it.

However, it cannot be separated from the colonial agenda so pervasive at the time. In fact, although Antarctica was uninhabited by humans, the concept of terra nullius was frequently evoked throughout history to dispossess indigenous peoples of their land, for example in Australia.

Nationalism, scientific interest, political and economic motivations, not to mention the race to a series of firsts among European countries to erase or claim parts of the map, were the agenda behind many of these expeditions.

The unexplored potential of Antarctica offered newer states like Norway, Australia and the USA the opportunity to prove themselves on the global, imperial stage, and more established imperial powers, like Britain, a chance to assert their imperial authority at the same time it was being challenged in colonial territories elsewhere.

The journeys mentioned here were fundamentally colonial, in that what was learned or taken from Antarctica (and stops along the way) was interpreted through a European, upper-class lens.

This view gained from a handful of well-known explorers, frequently fails to mention the working class contribution to these expeditions, as well as earlier discoveries by less titled naval journeys: between 1750-1920, over 15,000 people visited Antarctica.

Away from European expeditions, Oceanic people were most likely the first, ‘humans to set eyes on Antarctic waters’ if not land going back to the seventh century. Māori people were part of this Heroic Age too, as experts in navigating these seas or replacing members of the crew at times when needed.

It is a long connection between Oceanic people and the Antarctic which still exists today.

In 2013, a pouwhenua (or carved post) called Te Kaiwhakatere o te Raki (the Navigator of the Heavens) was erected at Scott Base. It reflects the long association between Māori people and the land.

The mighty powhenua, navigator of the skies, lit up under the #Aurora around #ScottBase. Epic pic by Keith Garrett! pic.twitter.com/QL7OAfNxko

— AntarcticaNewZealand (@AntarcticaNZ) August 6, 2016

The climate emergency

The issue of exploration and colonial expansion in Antarctica is also inseparable from issues around resource extraction and the current climate emergency.

Under international law, Antarctica is deemed a “land of peace and science”, where militarisation, dumping of radioactive waste and mining are banned and international scientific cooperation is encouraged. Yet, as the resources we depend on become increasingly scarce and technologies for resource extraction in previously hostile territories become more readily available, this has increasingly come under threat.

Additional words and research by Connie Churcher and Nathalie Cooper