Lagos, October 1, 1960. The multi-coloured bunting and posters adorned an already excited multi-hued metropolis – as if you could artificially imbue Lagos, the city of speed, style, and sizzle, with any more kinetic excitement. Well, the street decorations were merely a symptom of a more pervasive excitement, organically accompanying the events leading to Nigeria’s entry into the league of Independent nations.

Lagos had been the site of the formal creation of the nation of Nigeria, with an amalgamation ceremony held at the Supreme Court Building at Tinubu Square, in the centre of Lagos Island, at 9am on January 1, 1914. The Governor-General of Nigeria, Sir (later Lord) Frederick Lugard, had presided over a ceremony attended by 200 guests, after which he hurriedly boarded a train to Zungeru, in the North of Nigeria – the short-lived capital, which he (Lugard) had ironically insisted on – for another ceremony which was held on January 3, 1914. By the way, Lugard never spent much time at Zungeru and in fact the Government House at Zungeru was subsequently relocated to the more accessible Lokoja. Lagos, where a palatial Government House had been built in the early 1900s, became Lugard’s operational base for the rest of his tenure. This of course is an aside.

Lagos had been the first British Colony in what was to become Nigeria through the instrument of a treaty of cession in 1861. While there had been questions about the efficacy of the treaty itself, the protests ebbed when the new Governor of the Colony, Commander Henry Stanhope Freeman, pointed his ship’s cannons on the city, almost symbolically asking the protesters to speak louder. The protests quietened down as the King and Chiefs of Lagos, with some measure of trepidation, remembered the last time they had encountered those cannons – in 1851, when King Kosoko had been deposed and a British Consulate established on the Island. British influence soon spread in the hinterland of what was to become Nigeria through the parallel (and sometimes contending) efforts of the Royal Niger Company between 1879 and 1899, and the Oil Rivers (later Niger Coast) Protectorate administration between 1897 and 1899. The treaties were either preceded or tinged in aftermath with military coercion. A quote from a Lagos newspaper aptly encapsulated the efficacy of the coercive infrastructure with this line – ‘… the Maxim Gun inspired profound respect’.

All of these thrusts of expansion of influence converged in 1900 with the establishment of Protectorate Governments in Northern and Southern Nigeria, as well as the Colony of Lagos – the Royal Niger Company having been divested of its ‘interests’ with the payment of the sum of £865,000 and an annual Mining Licence. It is important to mention that the Royal Niger Company relied on treaties with communities in areas contiguous to the River Niger, which was affirmed by International agreement at the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 (representatives of the African communities being ‘unavoidably absent’, by the way). Thus, the oft-used description of the Royal Niger Company owning / selling Nigeria is patently incorrect, since the larger mass of territory was in the hinterland, beyond its purported areas of influence.

In any event, the series of conquests between 1900 and 1906, and the later discounting (by the UK Parliament no less in the Ormsby-Gore report to parliament, 1937) of the so-called treaties procured by the Royal Niger Company, also raise questions (admittedly academic at this point) about what exactly constituted the territories ‘owned and controlled’.

The legalities (and moralities) aside, all of these territories were progressively merged in 1906 (Lagos and the Protectorate of Southern Nigeria) and 1914 (Protectorates of Southern and Northern Nigeria) to create the monolithic geographical and political entity known as Nigeria – a hulking landmass of 330,000 square miles with an immense reserve of human capital and natural resources.

If Nigeria could be described as commercial enterprise, it certainly lived up to expectations. By 1918, palm produce, its main export, generated revenue of £2,704,446; tin, which was discovered in 1907, generated exports worth £1,704,443; groundnuts earned exports totalling £920,137; and cocoa, £235,870. Total imports and exports in 1918 came to £17,883,256 [source: Nigeria Handbook 1919].

The new country slowly came together with the infusion of colonial administrative systems and the gradual denudation of traditional institutions that were deemed to conflict with the ‘new order’ – especially traditional theological institutions. Traditional institutions of governance were tolerated as long as they aligned with the new paradigm of governance, and were in fact adopted as governance agents via Lugard’s model of the already established ‘Indirect Rule’ system. Where conventional monarchies were absent (in vast swathes of Eastern Nigeria, the Niger Delta, and the Middle Belt), monarchies were simply imposed by the stroke of a pen on a piece of paper known as a ‘Warrant’. Of course, a few people were upset by this – notably the women of Oloko, Aba, Ikot-Abasi, and other communities, who rose up in protest at taxes imposed by the new ‘Kings’ and indeed against the monarchical imposition itself. This culminated in the famous Aba Women’s War of 1929.

There were other wars, this time sanctioned by the colonial authorities; the Nigeria Regiment saw action in Cameroon and East Africa during World War 1 (1914-1918), as well as in East Africa and South-East Asia in World War 2 (1939-1945).

In 1945, two unsanctioned ‘wars’ took place in Nigeria though. The first was the Market Women’s Strike, protesting unfair price controls, followed by the first General Strike by the Nigerian Trade Union Congress, agitating for a cost of living allowance.

A new cadre of educated Nigerians had been emerging by the 19th century and increased significantly through the 20th century. These ‘elite’ Nigerians led the nationalist movements that started out by protesting some colonial policies, notable amongst which were the Aboriginal Rights Protection Society, and the People’s Union – the first political association, formed in 1908 in protest against water rates.

Voting rights were granted for the first time in 1920, in time for the Lagos Town Council elections, after an initial abortive demand by the National Congress of British West Africa held at Accra earlier that year. This was followed by Legislative Council elections held in Lagos and Calabar in 1923, which were dominated by the newly-formed Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP). The NNDP,headed by one of Nigeria’s prime nationalists, Herbert Macaulay, swept the Lagos polls, with two lawyers, Eric Moore CBE and Egerton Shyngle, and one medical doctor, Curtis Adeniyi-Jones, emerging victorious. In Calabar, a lawyer, Ata Amonu, won the sole seat available. The Nigerian ‘elite’ had arrived.

The quest for Independence was but a mere whisper in the first two decades post-amalgamation. Yet there had been indeed been a loud elite voice, even before the amalgamation. The irrepressible Reverend James ‘Holy’ Johnson made his views quite clear as to the future of colonialism in Lagos and other territories, i.e. an immediate end. As far as he was concerned, the only good that imperial intervention had brought to Africa was the Church and, even with the Church, he had his strong criticism (no surprise that he was later denied promotion to the vacant Bishop’s chair after the incumbent Ajayi Crowther’s death). Johnson’s exertions aside, nationalism emerged slowly, with specific demands rather than wholesale agitation.

One of the more radical movements was the Nigerian Youth Movement (NYM), which appeared in 1933 to protest for high quality tertiary education for Nigeria, and segued its demands into more sweeping nationalist aims. This message appealed to the populace, and the NYM – at one stage consisting of some of the brightest young stars of the educated elite – such as Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe, Dr Akinola Maja, Dr Kofo Abayomi, H.O Davies QC, Obafemi Awolowo, journalist Ernest Ikoli, Samuel Akinsanya, and others – dominated the Lagos polls in 1938.

After the Second World War, and especially with the strikes of 1945 and the consequent Independence of India and Pakistan in 1947, real agitation towards Independence for Nigeria swelled from a quiet murmur to hypothetical expression in the popular press. There arose a more bold-faced expression of discontent against inequalities inherent in the colonial system of governance.

Segregation had been made law by Lugard’s Town Planning Ordinance of 1917, which made it a criminal offence for a European to reside in the ‘African Quarter’, and this spilled over into public services and spaces, such as hospitals, clubs, and even some churches, where Africans were denied access. This segregation came to an end following the Bristol Hotel incident in 1947. A black British civil servant, Ivor Cummings, was denied access to the popular hotel based on his race, resulting in a protest organised by the Lagos elite. The protest caught the attention of Governor Arthur Richards, who finally issued the rescission of the colour bar in Nigeria.

While Nigeria had been spared some of the bloody nationalist struggles seen in some other colonies, notably Kenya, there were outposts of state-sponsored violence. There had been the Aba Women’s Protest, as referred to earlier, in which scores of protesters had been shot dead. In the post-war era, there was the Iva Valley Miners Protest, which resulted in several striking miners being shot to death by the Colonial Police.

Nigeria had been federated into two parts in 1939 – the Northern and Southern Provinces. In 1946, three regions were created via the Richards Constitution. A further constitutional conference was held in 1950 and a new constitution emerged in 1951, administered by Governor John McPherson, with regional legislatures and by 1954 (after another constitutional review) parliaments, and administrative responsibility by parliamentarians emerged.

From 1950, Nigerian women were allowed to vote for the first time, starting with the Lagos Town Council elections, from which the first woman to win an election in Nigeria emerged; she was Mrs Henrietta Lawson. Ironically, Mrs Lawson was the niece of the legendary nationalist, Herbert Macaulay.

In the interim, the nascent nationalism of the post-WW2 era was announced with a loud bang by a motion in Parliament for self-government, introduced in 1953 by the erstwhile firebrand journalist and fearless nationalist, Anthony Enahoro. The motion was defeated; however, the cat was out of the proverbial bag, and the clock now ticked towards the inevitable.

Four years of manoeuvring by the three main political parties – the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) headed by Nnamdi Azikiwe, the Northern People’s Congress (NPC) headed by Sir Ahmadu Bello, and the Action Group headed by Chief Obafemi Awolowo – eventually came to a head in 1957, when Samuel Akintola of the Action Group moved for self-government in the same year. This motion was amended and carried for self-government by 1959. At the Lancaster Gate London Constitutional Conference of 1957, the delegates moved for Independence in April 1960. By 1959, the final Constitutional Conference agreed that October 1, 1960, was to be the date for the Independence Ceremony, with elections to be held in December 1959.

The elections were bitterly fought, and the spectre of ethnic conflicts subtly characterised many of the electioneering campaigns; there were complaints of manipulation, violence, and suppression. However, the elections proceeded and were concluded with minimal contention as to the outcome: the NPC, now headed by Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, emerged victorious via a coalition formed with the NCNC. Balewa became Nigeria’s first Prime Minister, and Azikiwe became the first Nigerian Governor-General. A formal motion for Independence on October 1, 1960 was moved by Tafawa Balewa in parliament on January 16, 1960, seconded by Raymond Njoku, and unanimously passed.

The political parties for a time put aside their long-standing differences and prepared for Independence. The most important thing was for Nigeria to gain its Independence, and for its indigenes to exercise the agency in their own affairs that had been lost almost a century before – starting from Lagos. Nigeria held incredible promise, not just for its citizens or for Black people all over the world, but on the global plane. Its immense potential in human and material resources, comprising a numerically substantial, vibrant, highly skilled population, as well as a surfeit of resources, made it stand out as ‘the one to watch’. For ordinary Nigerians, this was beyond a joyous prospect. Nigerians yearned for a chance to enjoy the opportunities existing in a modern nation state, which the campaign promises of politicians had assured them were their birth right. Hence the excitement in the cities, and even in villages and hamlets – from the creeks of the Niger Delta to the dusty Sahelian outposts of the North – was quite understandable.

Princess Alexandra arrived in Lagos shortly before the Independence Ceremony as representative of the Queen, who was unavoidably absent. Nigerians were content; much as they loved Queen Elizabeth – having welcomed her in droves during her state visit in 1956 – all they wanted was Independence, and Princess Alexandra or any other representative was more than welcome for the purpose of formalising the Independence process.

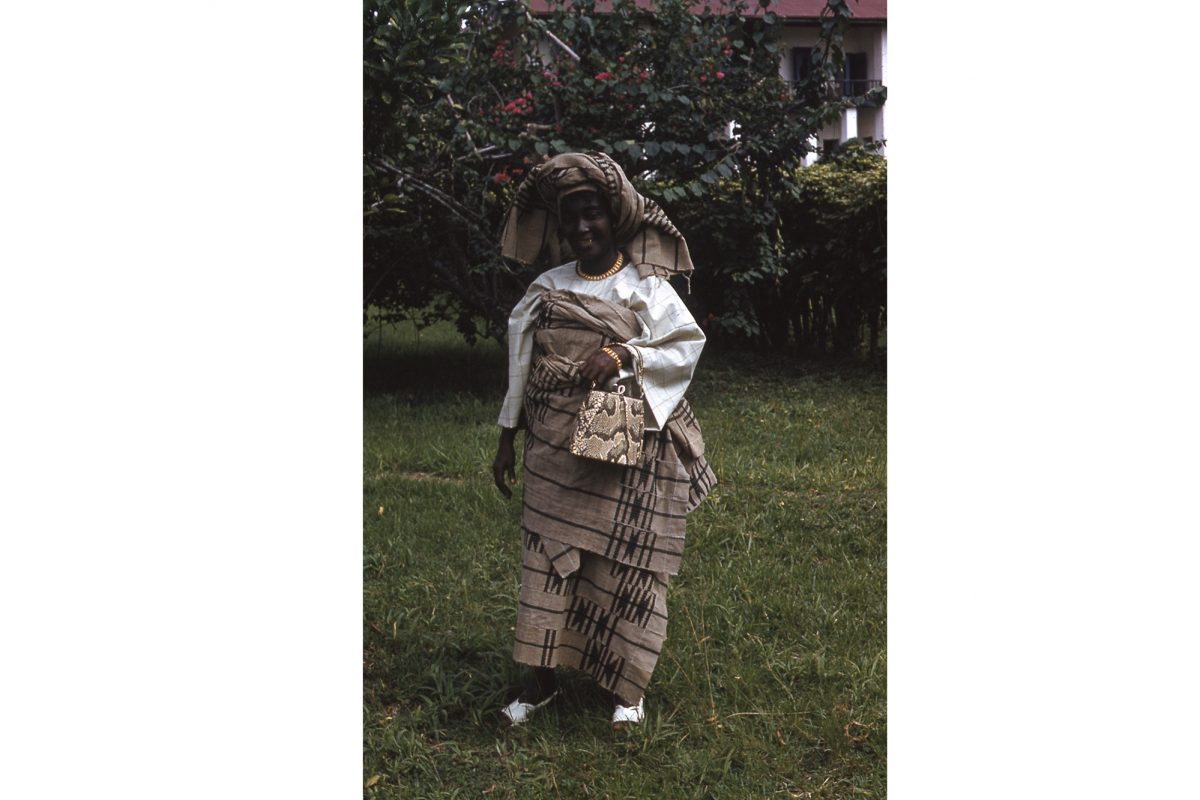

A series of events followed, including a State Banquet at which the great and good waltzed to the tunes of Nigerian Big Band Highlife, which in itself had been controversial. The Princess had wanted the music of Edmundo Ros, a British-Caribbean Big Band star, and colonial officials tasked with organising the event had feverishly laboured to see that her whims were satisfied. However, the Nigerian Union of Musicians – in keeping with the pervasive nationalist spirit – were less than impressed, and had demanded that Nigerian musicians be hired to perform – and they won. Dr Victor Olaiya, the press-styled ‘Evil Genius of Highlife’, took to the stage on the night. Other stars of Nigerian music entertained at several other venues, urged on by gaily-dressed revellers, brimming with pride at the dawn of a new age. Those of a more sedate temperament attended church and mosque services, where they nodded their heads to sermons exhorting the new leaders to govern wisely and indeed thanking their god, in whatever language the preachers adopted out of the hundreds available, for this great blessing bestowed on the new nation.

The Independence Ceremony took place at the Racecourse, in Lagos, where the Prime Minister took the oath of office. Princess Alexandra read the Queen’s address, congratulating the new nation on its freedom. Of course, the Queen would remain the ceremonial Head of State, but the de facto power now lay in Nigerian hands. All of these events culminated with the lowering of the Union Flag for the last time, and the raising of the Nigerian Flag for the first time. The flag had been designed by a Nigerian, Michael Akinkunmi, and was raised to the sound of the new Nigerian National Anthem, which had been composed by a British duo.

Nigeria had become an independent nation, and the parties carried on for days all across Nigeria, and rightly so. The simmering questions relating to political identity, and the complex conundrum of managing a humongous and diverse entity with over 300 ethnic peoples with varying degrees of compatibility, remained moot, as did the ominous issues surrounding the economic front – with Nigeria running a deficit economy from 1955, with foreign reserves falling from £562m in 1955, to £343m by 1969 [source: Falola and Heaton].

All of these would be dealt with later; for now, it was time to celebrate the dream of an Independent nation. The date was October 1, 1960.

Ed Emeka Keazor, August 2020 – All Rights Reserved