Have you ever wondered how the Horniman got its objects?

Who brought them here, and why?

I’m here to help answer some of those questions! I volunteer in Anthropology’s collection of English charms and amulets, which has a lot of pieces from a man named Alfred William Rowlett.

He came from the Cambridgeshire town of St Neots and, between 1904 and 1933, he sold the Horniman dozens of items that he had found as part of his town’s rural culture.

What do you think of when you look at the objects in the Horniman’s cases? What do you imagine of the people who collected them?

Do you think of a Victorian, professorial man with a tweed jacket and pipe?

How about a Victorian dustman with a bin and broom?

The picture above is from St. Neots The History of a Huntingdonshire Town, 1978. It shows Rowlett, who worked as a Dustman for the local government.

Bert Goodwin, a historian and local of St Neots, remembers Rowlett, and wrote about him for the St Neots Local History Magazine’s 2011-12 winter edition, including this picture of Rowlett and his dustbin making his rounds.

When looking up Rowlett in the 1881 Census I found he was in work as a labourer by the time he was 13. He went on to become a businessman, as well as a Dustman, with an antiques shop, and worked with the Horniman in a professional capacity.

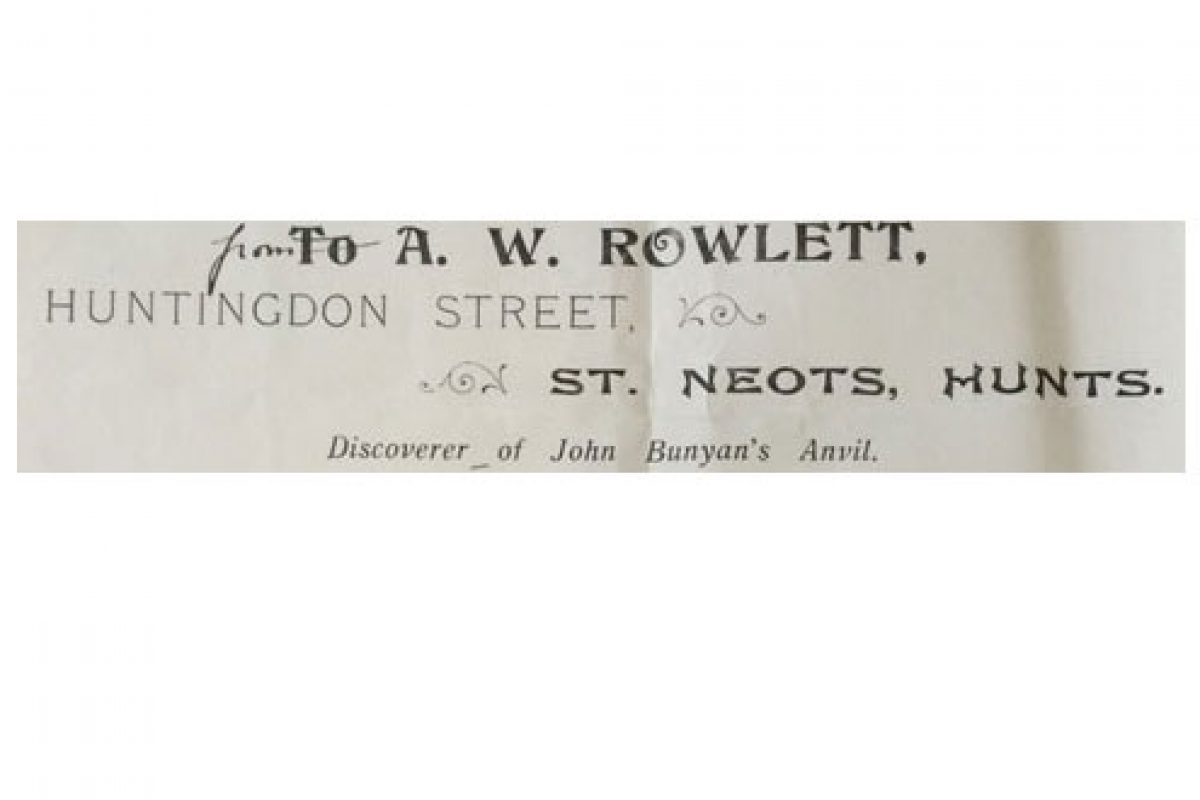

He even had his own official stationery that he used to write letters and invoices to the Horniman.

Here is how his letterhead looked:

We don’t know how Rowlett started working with the Horniman but as a local, he had specialist knowledge and access to his community. This was undoubtedly part of the benefit of the Horniman doing business with him.

In a letter dated 6 May 1907, Rowlett noted that ‘my business is to find out and get all the necessary information I can get’ on objects destined for the Museum.

His research is still important for the Horniman, as the things we know about the objects he sourced came via his connections. The information would otherwise have been lost without his detailed descriptors.

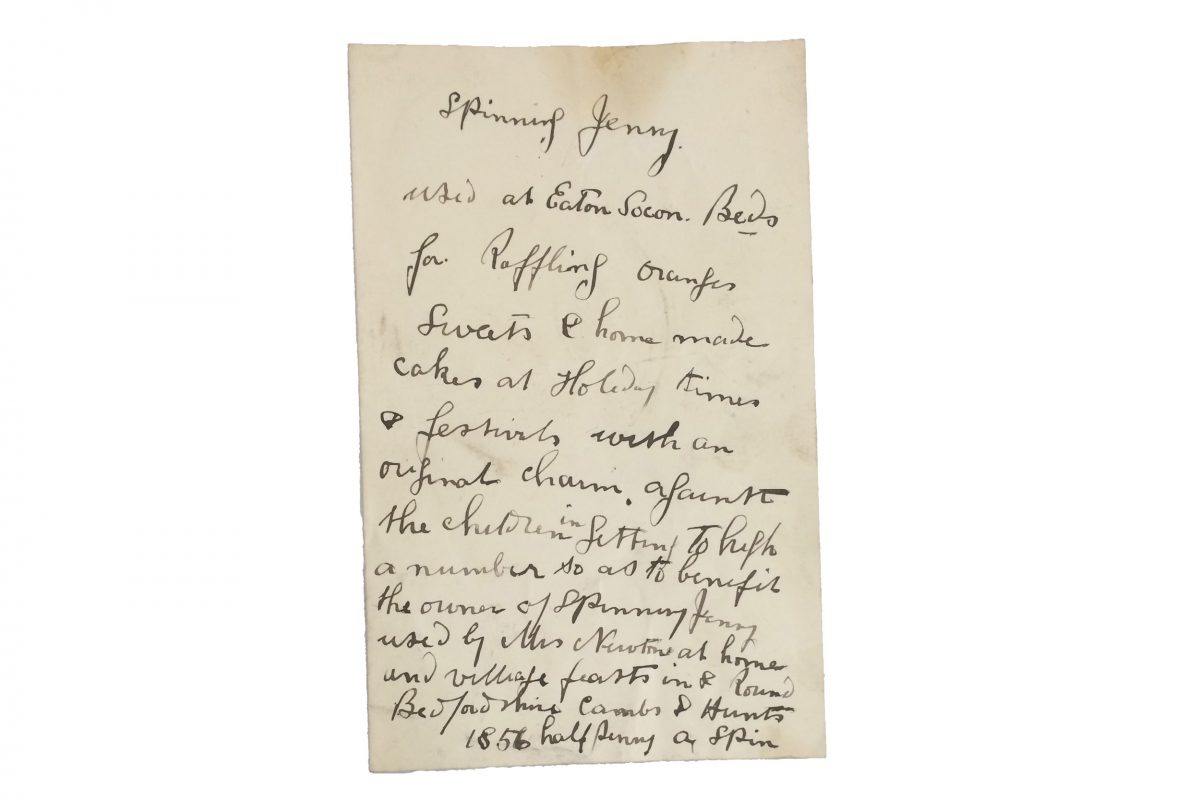

Here is what he wrote about a ‘Spinning Jenny’ (object number 7.199) as an example, with a transcription beneath.

Spinning Jenny.

used at Easton Socon, Beds for Raffling oranges sweets & home made cakes at Holiday times & festivals with an original charm against the children in getting to high a number so as to benefit the owner of Spinning Jenny

used by Mrs Newton at home and village feasts in & Round Bedfordshire Cambs & Hunts.

1856 half penny a spin

This is how the Spinning Jenny works:

You can see a piece of orange flint tied to the device – that’s the charm.

We know what that flint was for thanks to Rowlett, as well as precise details about how the Spinning Jenny is used. I thought the owner would’ve been caught out by cheating, but my Curator figured out that if you keep the stone against your palm and hold out the Spinning Jenny, nobody can see that you have it in your hand!

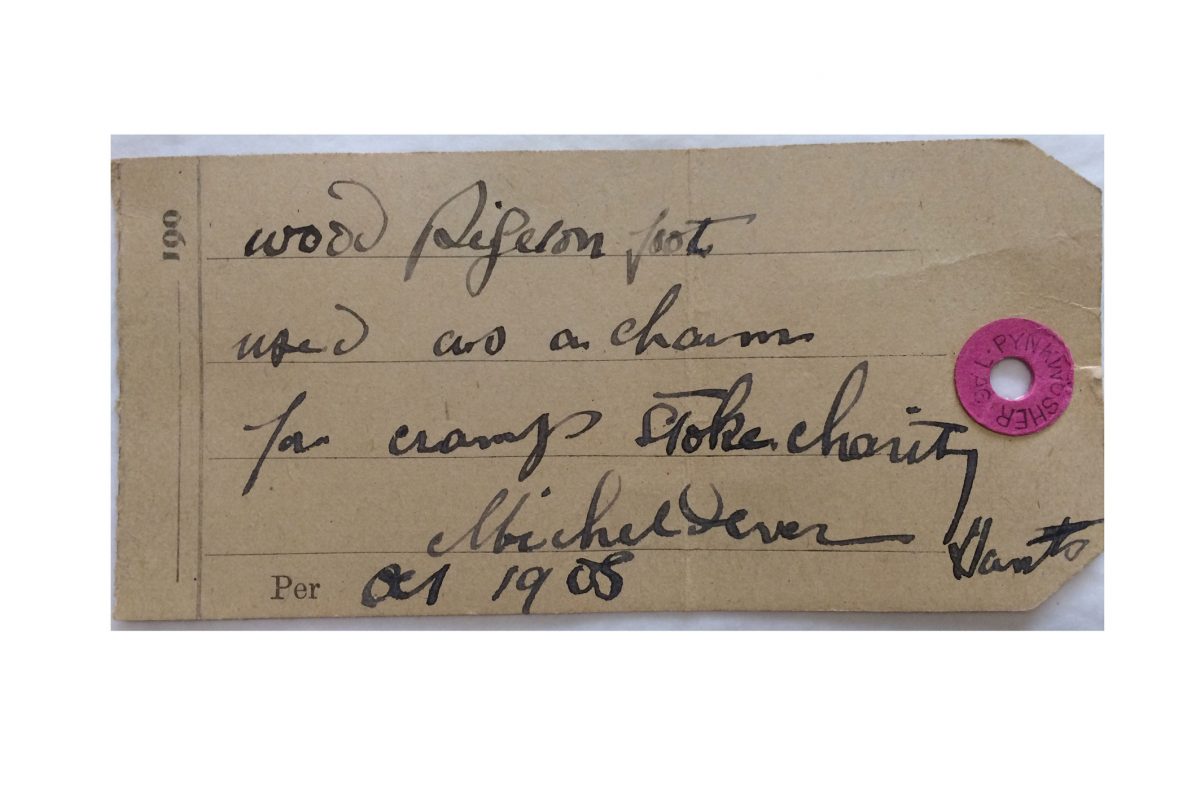

Rowlett would also make handwritten labels for artefacts that were entering the collection, and many of his labels are still stored with the objects. This is an example from number 9.41 in our collection, a wood pigeon’s foot that was used to ward off cramp.

A lot of the charms that Rowlett brought us are things from the natural world that people associated with various curative powers.

It may seem strange today, but the idea was that wood pigeons never get foot cramps. If I carry a wood pigeon’s foot, maybe that will protect me too. If you have ever heard of someone carrying a lucky rabbit’s foot, it’s not too far a leap from practices today.

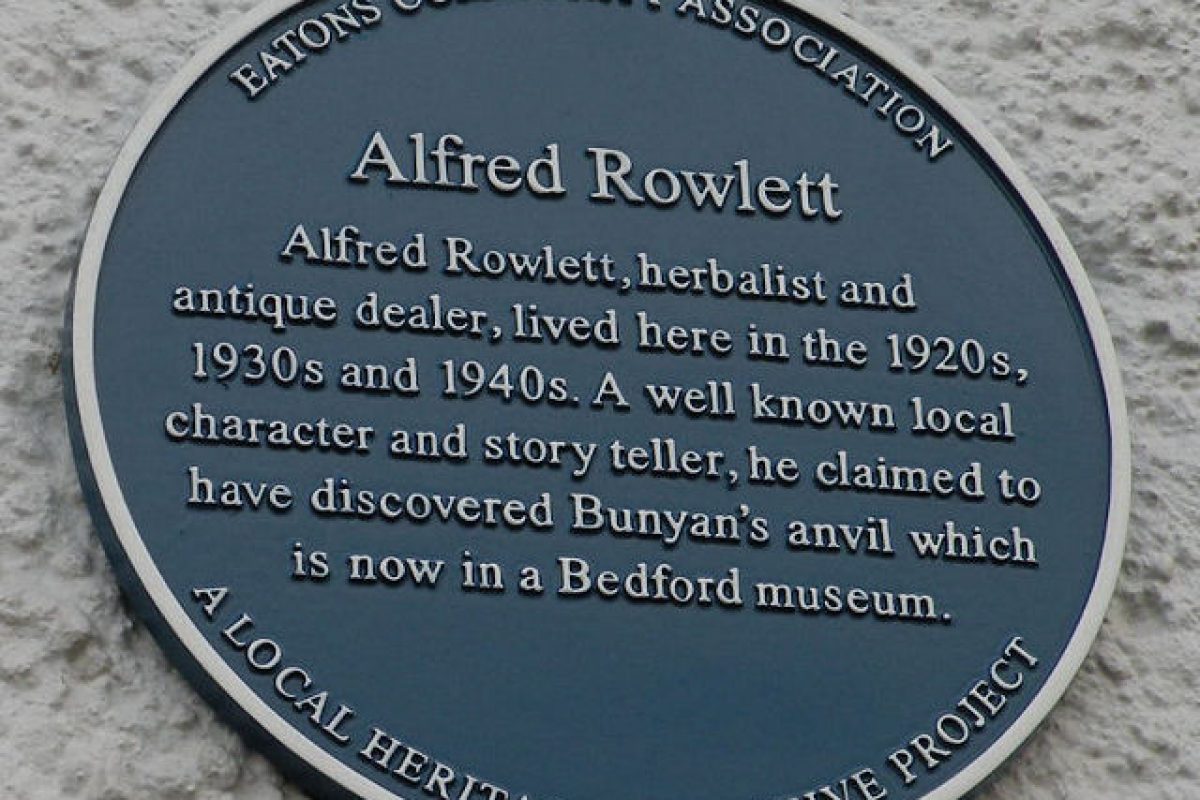

Rowlett’s community of St Neots still remembers him as someone to go to for these kinds of all-natural remedies for health problems.

Local historian Rosa Young transcribed several adverts from a 1900 issue of a local paper for the St Neots Local History Magazine’s, which included an old advert that Rowlett had put in the paper for his own special patent medicine.

It cured everything (naturally) but Rowlett’s neighbours did come to him seeking his medical expertise.

Bert Goodwin, the local historian who photographed Rowlett, recounts that when he was a child he had a wart on his knee cured by Rowlett:

He cut a small twig from a bush which he called ‘Joseph’s Thorn’, which he shaped into a spatula, and then made his mark on the wart X. “There,” he said, “it will be gone by the next full moon.”

Strangely enough, I forgot about it, but when I next looked it had gone.

Because of Rowlett’s work at St Neots, the local historical society put up a Blue Plaque for him.

Like the wood pigeon’s foot above, many of the objects that Rowlett brought to the Horniman were considered to have health benefits.

The charms I’m studying were used by real people who believed in them, and used them to solve a variety of different problems.

Ironically, Rowlett – with his Joseph’s Thorn for curing warts – thought that some of the charms’ owners were ‘eccentric’!

I don’t know about you, but I have lucky charms. Millions of people all over the world believe in the power of objects. In the Horniman’s World Gallery, you can find charms from all around the globe, including those collected by Rowlett in the European displays.

If you’d like to see what Rowlett brought to the Horniman, you can find all of Rowlett’s objects online.