As a Collections Management and Documentation Trainee at the Horniman, I have been lucky enough to encounter many fascinating specimens in the Natural History collection. One in particular is the western rockhopper penguin.

The sheer variety of the collection has meant that I’ve learned to handle and pack away everything from alligators to anteaters. It has been an invaluable learning opportunity, and the need to think about new packing solutions has allowed me to get a closer look at things I would never get the chance to see otherwise.

I’ve gained a new appreciation for whole swathes of the natural world (even the slightly terrifying tarantulas on display), but there is one specimen that stands out as perhaps the cutest thing I’ve packed: the western rockhopper penguin.

Nature + Love

As part of the Nature + Love project, we are taking all of the specimens on display out of their cases in preparation for an exciting re-development of the Natural History Gallery. This is known as decanting. This will involve refurbishing the historic showcases as well as a complete redisplay of the space — with an emphasis on accessibility and a call to action to protect the natural world that we all love.

Another aspect of Nature + Love is redeveloping areas of our wonderful gardens to create a new sustainable gardening zone and play area — linking together both the Natural History Gallery and the nature we are lucky enough to be surrounded with at the Horniman. It is this project that gave me the opportunity to get a closer look at this specimen and find out a little more about it.

The Penguin in question

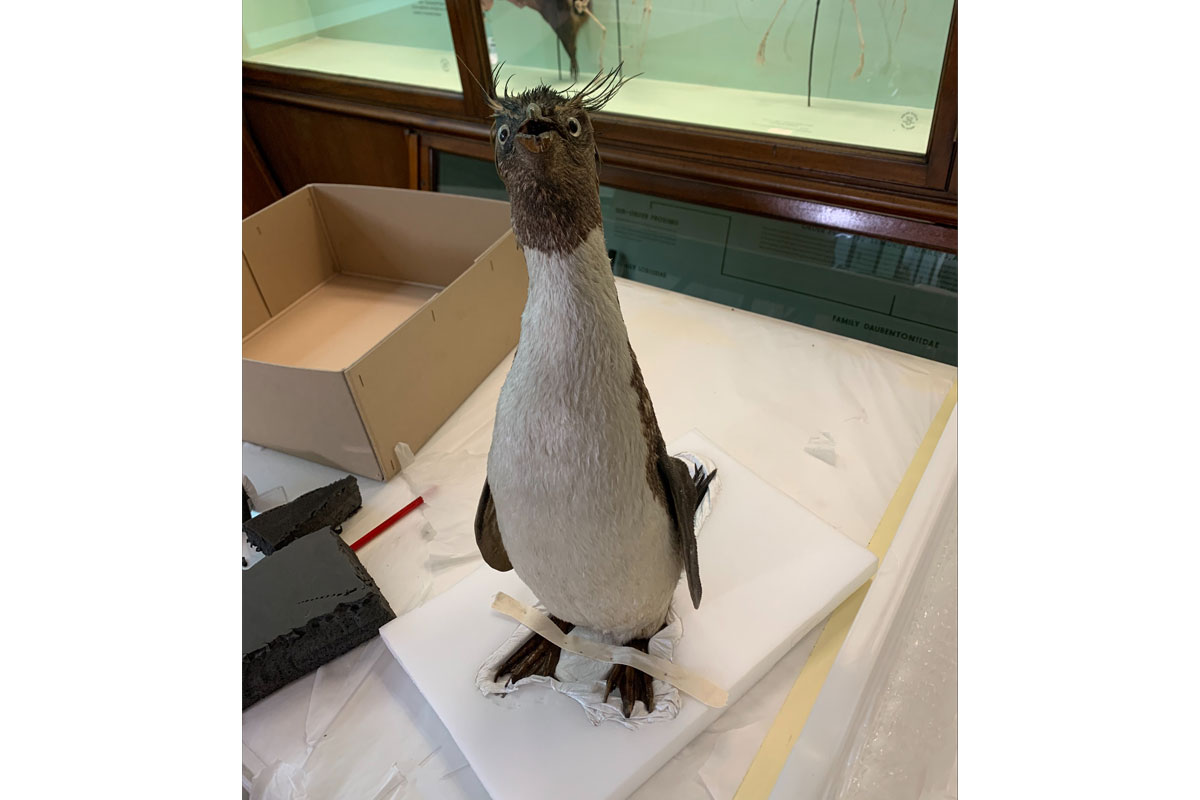

If you have ever been to the balcony of the Natural History Gallery, you may have noticed this taxidermy peering over at you through the glass of a wall case, where it has stood for many years. In the wild, you would find western rockhoppers in the southern hemisphere, especially around the Falkland Islands but sometimes even as far as New Zealand.

Looking at the penguin’s record on the Museum’s database, I found out that the penguin was part of the S. Prout Newcombe Collection, which contains over 1,000 natural history specimens. These range from birds like our rockhopper to corals and reptiles, so clearly Newcombe had quite varied interests.

I also learned a little more about rockhopper penguins in the wild, as the record included information like the specimen’s conservation status. Today, western rockhopper penguins are classed as a vulnerable species, which means their numbers have decreased in the wild. In fact, the number of breeding pairs on the Falklands Islands has fallen by 87% since 1932.

The penguin has, therefore, served as a representative of a species we are at risk of losing for all the years it has been on display.

The process

The first step in the decant process is to open the case and get a good look at how the specimen has been mounted. Surprisingly, I discovered that the penguin was balanced in the case using a large metal spike. This meant that its feet were not working at all to keep itself upright, and I had a wobbly penguin on my hands.

I laid the penguin down in a large plastic tray buffered with tissue to get it back to the packing area, but I knew that the best thing for the specimen’s delicate feathers would be to pack it standing. If it could be balanced with foam, there would be fewer points where anything would have to touch it, and possibly damage its feathers.

I began constructing foam supports and lined anything that might touch the penguin with a material called Tyvek, which is a smooth fabric that minimises abrasion. I also cut out a base for the box, drawing around the penguin’s feet and cutting out the shape so they could slot in neatly, and placed some blocks to cushion the specimen should it move about in transit.

The penguin had not yet been selected for the redisplay, so I wanted the packing solution to be suitable for long-term storage at the Horniman’s Study Collections Centre (SCC) if needed.

The SCC is where we store most of the objects that are not on display; amazingly that is around 95% of the Horniman’s collection. However, this penguin’s luck was about to change. Once it had been removed from the case and we could get a proper look at it, we were greeted with a much more engaging specimen than we could have predicted.

New discoveries from decanting

With its feet on the floor and side-on stance, it was quite difficult to see the penguin’s inquisitive expression while in the case. However, once decanted, it was impossible to ignore and the curators decided to add the penguin to the list of specimens they will consider for the new gallery display. I’m almost certain that the main reason for this change in plan was because it would add a great deal of educational value to the gallery, but I think it was simply too adorable to resist.

Something this role has taught me is how different something can look once it is removed from a case. While packing away specimens we have decanted, I have seen fascinating details I hadn’t noticed before. For example, I had never appreciated just how delicate the wings of the bats on display were, or how many rows of teeth a shark had.

It has been a real privilege to interact with natural history specimens during the decanting process, and I can’t wait to learn even more about our collection as the Nature + Love project continues.

However, it will take a great deal to overtake this wonderful rockhopper in the cuteness contest!

Part of our Nature + Love project, which is made possible with The National Lottery Heritage Fund, thanks to National Lottery players.